Trek Matthews is a young Atlanta-based artist whom I have had the pleasure of getting to know through his work with Living Walls. Through complete coincidence, Tim Hans ran into Trek on a Brooklyn rooftop earlier this year. Tim photographed Trek for the latest in our continuing series of photo-portraits of artists by Tim, and Laura Calle met up with Trek back in Atlanta for an interview. – RJ

Laura: Let’s talk about your experience as an artist who also works on the streets. How did you start painting outside?

Trek: I’m gonna tell a short story to answer this. Basically one summer, when I recently had moved into this city, I think it was the second year of Living Walls but it was the first year that I heard of it. There was a call for volunteers and I got involved and it was rad. I assisted for Gaia and Nanook and Sam Parker and it was super super rad. I had seen their work before cause I had always been passively interested in seeing what they were doing at that time. I decided to keep going with it, and kept hanging out and trying out new things. At that time I was part of the graphic design program at a university, and then shifted the focus to drawing and started to bring that to a certain direction, with no intention of painting, until Living Walls approached me with a project. Until that point I had not done anything large at all, I hadn’t painted on a wall, or at all. I started practicing and experimenting anywhere I could, then I did my first wall a couple of weeks later. So it pushed me really quickly. Then I tried to adapt my aesthetics to different situations and aspects.

L: How do you think you participate in this contemporary movement, which going outside to the streets art, do you see yourself as an illustrator, a street artist, none or all of the above?

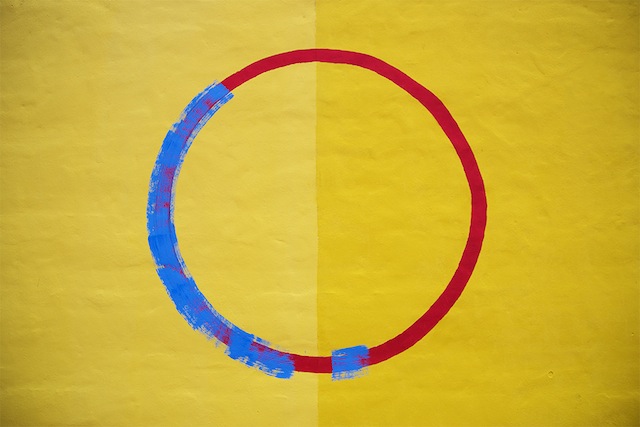

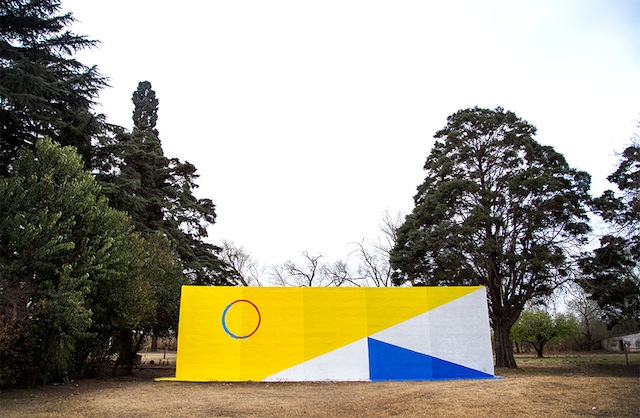

T: Yeah, I kinda just try to do a mix of anything instead of being a purist on any intent and that tends to include doing things on paper that I can push myself personally on a small scale and then how that translates to the public realm, whether its sanctioned or illegal, it’s always sort of interesting, to see how things aesthetically adapt to the public environment, or conceptually adapt to the public environment. So, with personal pieces I tend to go more with memory based objects or things that are purely based on what I have experienced or things that I remember, whether they be memories or fractions of memories, and when my work goes into the public I tend to look at how that area has progressed in a very subtle level. So it’s about my personal memory and what I experienced in that area even for the short time that I have worked there. So with things like public transit, public infrastructures, I try to see how they change the specific spaces I come across. So I like putting things both on paper or any sort of material, but I think the ability to react with the public is really good and to have a conversation with people that aren’t ‘art people’ and how they see things, how they react to things, especially now that I am pushing more towards a minimalized and abstract aesthetic.

L: How has your style evolved in the past few years?

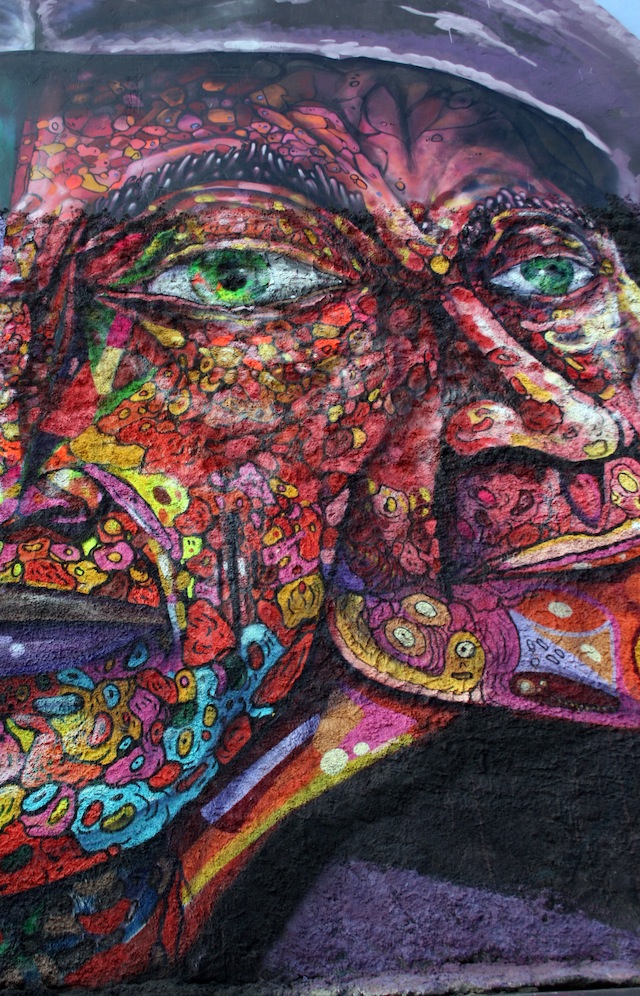

T: I was trying to focus on illustration and basically straight up drawing things, drawing anything from an animalistic approach, I liked that a lot at a certain point. I had basically not painted at all so I have always enjoyed deconstructing things and re-drawing them how I’d like to see them, but still pretty simple. I didn’t have too much concept so I tried to look into cultures in my area, the descending cultures of where I was from, and tried to branch out into other cultures without re-appropriating it too much. Just to keep it personal but try and still exhibit a culture that was here previously, so I kinda wanted to keep doing that for a while and got interested in color, cause I was just doing black and white and I wanted to do more color based stuff, therefore I had to start to focus into paintings or pushed ink. So that changed the subject into people and transportation and the process of moving in general. So I tried to make it more dynamic and minimal, I guess I started doing that earlier this year. I’ve been bouncing between doing things large scale and small scale, so I would go to location, like when I was in Spain I’d sketch something and then go and see how that it fits into the space, then bouncing that into paper and adapt that by adding more depth and trying to increase my speed.

L: Does the setting of where you’re working influence you?

T: To an extent, I like to have the composition fit what it’s on to a certain extent and then trying to base it on the loose history of that area, without getting to apparent or in your face, I like to keep it fairly loose and conceptual so that people can give it their own personal narratives or a narrative of that area. So if it’s not sanctioned, they are kind of just compositions that adapt to the area that I’m working on, but I just wanna quickly put it up. But if its sanctioned I want it to be relevant to the area, for example the piece I did in Bushwick in March, I wanted it to relate to the area and how it’s changed. I learned that the spot that I was working at was an area with high volumes of violence towards prostitutes, so I kinda wanted to look into that and keep it very loose, but with that I wanted to make it more powerful on the feminist approach. When I was sketching it, I was keeping that in mind, so the concept that I was going for and the composition reflected that local history.

Photos by Tim Hans