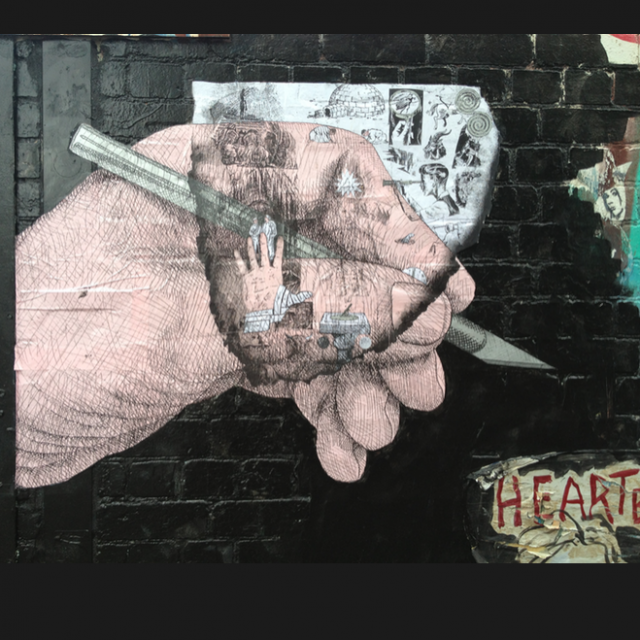

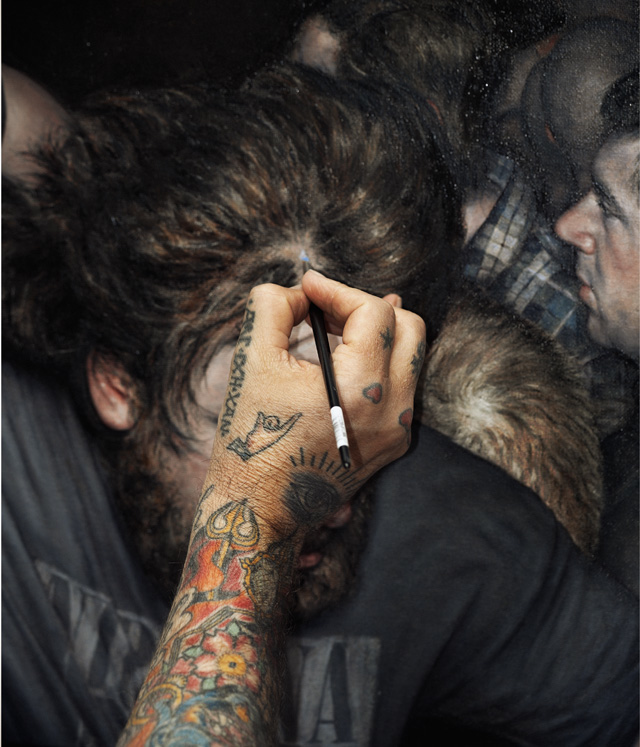

Logan Hicks is a forefather of the stenciling medium. With a background in printmaking, Hicks helped pioneer the use of multi-layer stencils to create strikingly complex portraits of urban environments. While many artists are satisfied with two or three stencil-layers to create images, Hicks has used up to 15 in a given piece. He is also known for his documentation of his adventures through the labyrinth of tunnels and pipelines in various cities around the world. Recently, he began incorporating figures into his pieces; contrasting hard architectural details with the softness of female figures floating through water. Hicks continues to explore the creative potential of stencils and the content they are able to illustrate. Tim Hans met up with Hicks last summer for our continuing series of photo-portraits of artists by Tim, and I interviewed him in anticipation of his upcoming solo show “Love Never Saved Anything” at 154 Stanton Street in New York City, opening March 7th at 6:30pm and running through March 19th (open 11:00am-6:30pm daily).

Caroline Caldwell: How did you get started exploring the tunnels and sewer systems in cities around the world? What interests you about it? What are some of the dangers? Any good stories?

Logan Hicks: Moving to NY is what really initiated the push the notion of going places that are ‘off limits’.

I grew up in the country, so I can remember checking out abandoned houses and stuff like that, but never really thought much about it. it was curiosity to see what was beyond the facade. When I moved to Baltimore, I poked around more and that’s when I came across the book ‘The Mole People’ which started me focusing on the city under me. Later I moved to San Diego, Los Angeles, and ultimately New York which is what firmly entrenched me in the idea of exploring places. Especially New York. To me NY has always been the quintessential city. It’s hard not to become amazed by the layers of the city.

I didn’t really know that there were communities of like minded me before moving, but I just ended up becoming friends with few people who shared my sensibilities. I suppose the default title is ‘urban explorer’ but I cringe at that title sometimes. To say you’re an ‘explorer’ sort of oversells it, but I guess saying that you’re a ‘really curious guy’ doesn’t really roll off the tongue. I just like checking out places and I like hanging out with the people that I explore with.

One you’ve managed to check various tunnels and buildings around the world though, it fuels the desire to see even more. Once you see what one subway system is like, you want to see the others. You want to see how it was made. Where it runs too. what is past that dark curtain at the end of the platform. Once you stand on top of a building crane 50 stories up, you can’t help but look up and want to get onto another. Part of it is that you just want to experience the rush. Part of it is that i just like to get away. As social as i am at times, i’m still an introvert at heart. I like to get away. To be unseen. To find quiet pockets of the city to go to. it helps keep me sane.

Stories? I’m sure there are a few, but the most memorable one was when I was exploring a tunnel out in Los Angeles with my good friend Jordan. We started walking into this round tunnel. It was maybe 8 feet wide. We walked in about 25 feet when I think I see something up ahead. Jordan was behind me so he didn’t see it, but I said ‘hang on’ and i yelled out ‘is anybody there’. After a second or two of silence a voice cracks the darkness with ‘yeah’. We were a bit startled cause it was just pitch black ahead and here this voice was up ahead out of our field of view, even with the flashlights on. I ask ‘you mind if we pass?’. “no” he says then follows up with ‘you ain’t got no camera do you?’. I’m a bit nervous at the question wondering if he’s going to mug us but I realize that it’s probably just some homeless guy who doesn’t want to be photographed during his lowest time. I say ‘yeah, but we aren’t taking pictures of people, just tunnels”. he gives a quick ‘ok, come through’ and we start walking. As we get closer we start to make out his silhouette, then as we get even closer we realize that there are actually two people. One standing, one sitting. The guy we talked too was butt ass naked, standing in the middle of this tunnel smoking crack not giving a fuck. There is no tunnel large enough to feel comfortable in as you walk past a naked man smoking crack. I had my hand on my knife the whole time and he ended up being fine. his friend was sitting down in the drainage tunnel letting the water pour over him as he smoked crack. I couldn’t help but think to myself, what is more crazy – us seeing two grown naked men smoking crack in a random tunnel – or the fact that they saw these two guys walk into a tunnel with a camera and never come back? That was probably the most odd experience I’ve had.

Caldwell: Your upcoming show will have a much stronger focus on the narratives of each piece and exploring themes such as old sailor’s superstitions. Can you talk a bit about this?

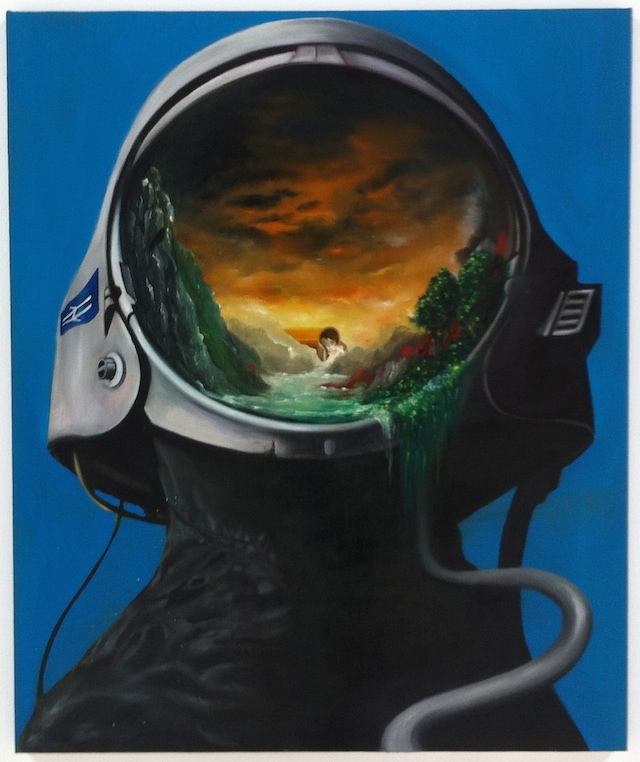

Hicks: Yes, the new work has evolved away from the architectural works that I’m known for. In the past I’ve worked from a more passive standpoint in my work. the architecture in my work was often contemplative, still, reflective. It was more of an internal thought. But last year though ended up being a fairly turbulent year for me. I had a string of bad luck that just tainted my daily life. Everything from finances, relationships, legal issues, personal happiness – everything. I was trying to salvage a few things in my life when I had a conversation with a friend of mine who said “at least you’re doing what you love”. I replied “Love never saved anything though”. That is the title for the show I am having in March – “Love Never Saved Anything” I started working from a more emotional point instead of intellectual. That is what led me to underwater photography. A good friend of mine in Long Beach offered a pool and herself as a model, so I took the opportunity to explore the medium. I fell in love with it. The drifting, weightlessness, floating model was sort of how I felt internally. It just felt like it was the perfect way to capture what I was going through – adrift in a sea of uncertainty. From there things just came together. I was connected with a great fashion designer out of Chicago who made dresses specifically for the next series of underwater shoots and I kept down that path. Along the way I came across various sailor traditions and superstitions and I was intrigued. There are so many obscure and odd traditions like ‘don’t cut your nails or hair on a ship’, or don’t talk to a redhead or you should shed a few drops of blood before boarding a ship for the season. There are hundreds of them, and some of them are more vivid than others, but I started to realize that these superstitions dealt with the same exact thing that every human in the world worries about – life, love, fortune, happiness, death. It’s the circle of life. It was the same thing that I was going through. So it just felt right to use these nautical traditions as a jumping off point to illustrate my own struggles. It has more of a narrative with these sailor traditions sort of providing the framework for the imagery for the work.

Caldwell: You’ve used the internet in conjunction with your art making for a number of years. You were active on some of the first internet forums and online dialogues about stenciling. Today, you make yourself a presence on social media so that people are able to observe a good deal of your artistic process. Would you say this has had any affect on the work you put out?

Hicks: It does. I think that especially when you have a technically demanding medium such as stenciling, the more you can educate the viewer on how you create the work, the stronger you make it. The aim is to help the viewer see the process and evolution of the work, from idea to execution. Ultimately it’s the work that needs to stand on it’s own, but it’s helpful if people understand how you arrived at the final result. So in that sense I find the communication critical to seeing the big picture. Ideally you hope that people can connect with every aspect of your work – the idea, the process, the execution, the medium, the story behind it, etc. For me it’s important to show people that the results of my work are not happy mistakes. It’s important that people see that you’re striving for something and that I’m working and working towards that vision. Seeing an obscure idea in your head morph into a physical painting is an interesting process.

Caldwell: To what degree do you allow your work to be left up to interpretation?

Hicks: If you’re making work that is so narrow in it’s scope then I just don’t think it’s very successful. I try my best to stay away from specific definitions. I might use a specific story, metaphor, experience, or tradition as a starting point for a painting, but it’s never the backbone of appreciation. It’s the inspiration for it.

If you need a story to go along with a picture, then I kind of feel like you’re more of an illustrator or story teller, but not a fine artist. Artwork is most successful work is when the viewer can connect with. If you’re telling the viewer what to believe, then what’s the point of making work in the first place? Successful art is nothing more than a mirror that allows the viewer to see themselves in. It’s a language that allows you to speak from your point of view that can convey the emotions that you’re feeling. So when I approach my work I try my best not to be so literal with the meanings. If you’re feeling a bit depressed, there are ways to imply that in the work. The colors you use, the strokes of color, the composition, the expressions of the models, even the title of the piece etc But if you have an artist who says “this piece of art is about when my dog Squeaks died and i was super sad, so i made this piece of art to remember squeaks” you just feel like their using art as therapy and you’re the unwitting ear that has to listen to them drone on about their life. I try to make work that speaks to the human condition. the cycle of life. Life, death, happiness, love and fortune. That is the pinnacle that drives most every decision we make.

I try to think as little as possible when I paint. Sometimes you need to think with your hands if that makes any sense. You just need to feel your way around the canvas.

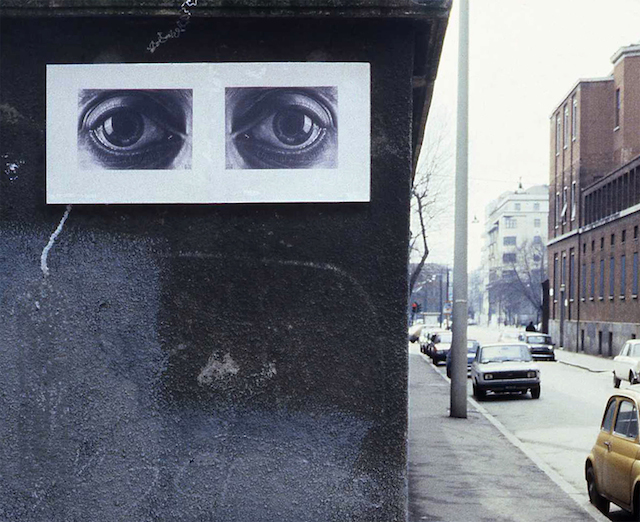

Caldwell: Do you think the street art scene is becoming formulaic, what with the seemingly abundant amount of legal walls, festivals and group shows, or is this still an authentic progression?

Hicks: Street Art is dead. The corpse of street art has wandered the streets trying to find a new label to wear without any success. The original actions, motivations and effectiveness of street art died long ago.There is some phenomenal work that is still produced that could be classified as street art in the fact that it’s art that is on the street, but I think that people trying to still claim that ‘street art’ is revolutionary or subverting the gallery model on it’s head is idiotic. Originally street art evolved because there was this in-between group of kids who didn’t do graffiti, but they didn’t fit into the gallery system. So they found a gallery – the street.

However, when a subculture or movement becomes self aware you can’t claim that it’s pushing the boundaries really. Once you’re self aware, then people start trying to define it. They start to impose these imaginary rules, protocols, and ideas. So now you can say that ‘this’ is street art, but ‘that’ isn’t. These days you have kids paying 40k a year going to art school trying to emulate what evolved in street art decades earlier. You have real estate developers that use street art as a handshake to the surrounding community to ease the transition of gentrification. You have street artists claiming that they’re raging against the machine while wearing Louboutin shoes at the opening. Street art has become a parody of itself. I’m not saying that the work isn’t good, but the definition of street art as an overall movement is antiquated.

If you look at artists like Aryz, C215, or Swoon, and you just think ‘that’s great art’. You don’t think ‘they are good for a street artist’. Good art should be timeless. But you look at some artists and you try to imagine them 50 years from now and the work doesn’t hold up without the street art label to carry it.

The definitions and classification of artists is something that artists shouldn’t concern themselves with. Artists should just make art. Labeling yourself limits how people perceive you. It limits the potential that you have. I’ve been included as a street artist over the years – and maybe I am – but I’ve never embraced it because I never want to feel limited. I just want to make art and I don’t really care if the tight jean fix wheel hipster likes it, or the 80 year old trust fund manager likes it. My focus is just making art that conveys the ideas and vision that I have. Labels and it’s definition is best left to others.

Caldwell: If you weren’t an artist what might you be doing with your time?

Hicks: Crime or drugs or laying in a grave rotting. There has never been a plan B.

Photos by Tim Hans