Faile recently returned from a trip to Mongolia sponsored by Tiger Translate, where they unveiled their latest sculptural creation and some street work. Over the past few months, Patrick McNeil and Patrick Miller (aka Faile) have been working closely with Mongolian sculptor Bat Munkh to bring this colossal piece to life in its permanent home. Faile was kind enough to invite me to their studio and talk about their experiences unveiling the sculpture in Mongolia and their thoughts on creating their first permanent piece. – Caroline Caldwell

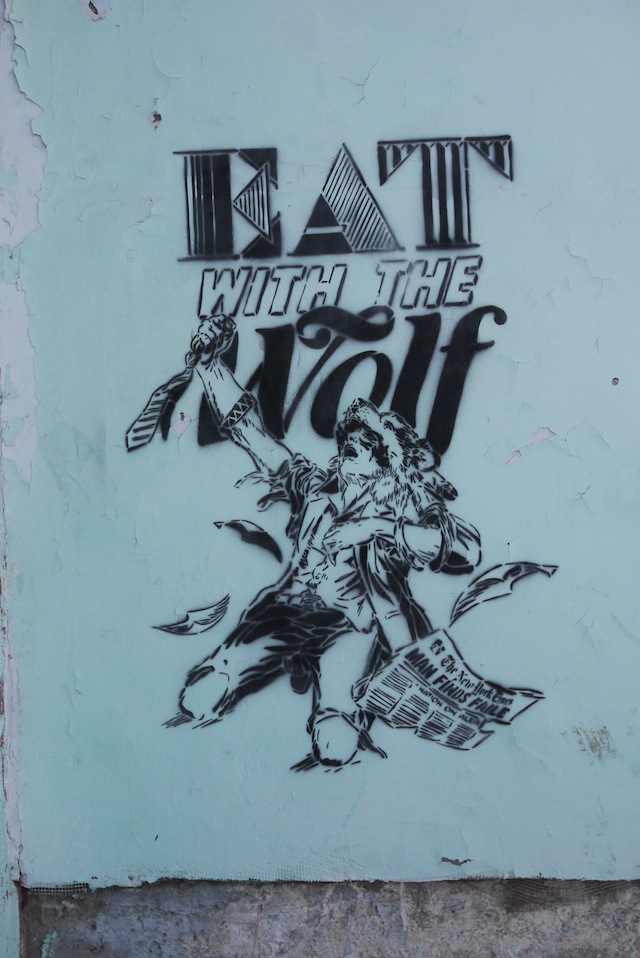

Patrick Miller: We made this sculpture, which is of an image we did in 2009 called “Eat With the Wolf” and it’s sort of this businessman tearing away a suit, wearing a wolf pelt. He’s placed in their national park, Ulan Bator. Behind the sculpture is this mountain preserve and then he’s looking on to all this new development. So this will all be a grassline, 1600 acre park. It’s wild to have a permanent sculpture in this city.

It’s pretty amazing. It really couldn’t have been a better sort of symbolic thing of what’s happening in Mongolia right now. Basically, they’ve come across all these minerals in mining, copper and gold, and the Russians and the Chinese are descending upon Mongolia to really try and mine the shit out of it. It’s sort like, what’s gonna happen to the city and how will the people actually benefit this? Or will the country just be mined for its resources and kind of left as a shell? So there are a lot of these issues going on there right now, which made this sculpture feel pretty timely.

This image came out of a series we did called “Lost in Glimmering Shadows” and it was sort of imagining if Native Americans had come back to the city today and retaken the land. This image was really about this crisis within of battling between greed and a connection to nature. So we’d been working on this sculpture for awhile on its own with Charlie Becker, who’s a sculptor we work with a lot, and Tiger Translate and the Mongolian Arts Council approached us and asked if we’d be interested in doing a sculpture out there which essentially led to doing that.

Patrick McNeil: We submitted a couple different ideas and this is the one that the arts council kind of gravitated to because of, I think, the wolf symbolism. We did a couple other things but this one just kind of resonated the best. There were a couple pitches that we did that got lost in translation, or it just didn’t make sense with the Mongolian culture.

It was a really tight timeline too, and we already had this sculpted since we’d been working on a miniature version of this one. So with the timeline and everything, this one seemed to make the most sense to execute in the 3 months that we did it in.

Caroline Caldwell: Do you think the Mongolian people will understand the Native American symbolism or do you think they’ll interpret it within their own culture?

McNeil: You know, if you look at their culture, it’s very similar to a lot of the symbols and things that weave through the Native American culture; with wolf being a power animal and horses, the shamanism, and even just the nomadic lifestyle.

Miller: They actually think that the Native Americans came over from Mongolia and Upper Asia. So yeah, I definitely think they’ll have a strong connection with that idea.

Caldwell: Why did you agree to do this project?

Miller: Sculpture is a big part of our practice and I think a large scale, permanent sculpture in a city was a really amazing opportunity. We were grateful for the ability to have that opportunity.

McNeil: The location too.

Miller: Yeah. Then it was like once we had landed on the idea for it, it all made so much sense looking at what’s happening in Mongolia. It’s one of the world’s fastest growing economies so they’re basically facing all these issues of modernization and materialism and capitalism. They’re gonna be in either a really great place or a really negative place coming out of this. The symbolism of the sculpture really seemed to make sense.

McNeil: I think the initial draw, though, was just the fact that it was in Mongolia. Mongolia seemed like a really exciting destination. Neither of us had ever been there, and it sounded fascinating. You always have this idea of Mongolia, like you’ll see horses and these vast open spaces and it sounded like a great place to visit.

Caldwell: Well, how was your time there?

McNeil: It wasn’t like what we were expecting because we never really ended up on the countryside, with our timeline.

Miller: We worked with a Mongolian sculptor there, Bat Munkh, who we collaborated on the project with. He basically interpreted the sculpture in large scale and then he worked on the base, which is a traditional Mongolian pattern. So we went back and forth through emails and photos, making all these corrections that needed to be done. Little tweaks like that.

McNeil: The city was fascinating. It’s going through crazy transitions, you know. They kind of just got their independence from the Soviet Union in the 90’s and they’re coming out of communism and shifting from a very nomadic culture to this crazy modern civilization. There was an insane amount of construction going on that I didn’t expect to see. Like you’d look out on the horizon and you could count about 60 cranes.

Miller: Yeah. Out here, out in this area it was just all cranes if you looked back.

McNeil: The other thing that was shocking was the pollution. You’d think that out there, in this country the size of Western Europe, with only 2 million people, that the air would be clean and fresh. And when you get out there you see that everybody is still burning coal. There are two huge coal factories that burn at one end of the valley and the air blows the smoke from the coal factories down through the valley, and at night everyone lights coal to heat their houses. So the air really fills with coal smoke. At night, when you look up at the skylights, you see like smoke in the air and it’s very strong. You can’t open your hotel window without there being such an odor presence.

Caldwell: Is this an area that has many other public works of art?

Miller: It has a fair amount of sculpture.

McNeil: Stately sculpture, like Soviet propaganda-style culture. A lot of that is dwindling. I think they just took the last Lenin statue down like two days ago. But they used to have a lot more communist propaganda Stalin-type stuff going on.

Miller: A lot of Chinggis Khan.

McNeil: Now they’re trying to build their own national identity. So a lot of that revolves around Chinggis Khan/Genghis Khan, so you’ll go to the state capital and there are huge sculptures of him. There’s a massive sculpture of him two hours outside of the city that I think is the largest or second largest sculpture in the world – I think it’s taller than the Statue of Liberty – and it’s him on horseback and then around him there are maybe 10,000 sculptures of soldiers on horseback. So they’re really pushing their Mongolian identity. You see a lot of sculpture and then there are some relics of the Soviet era.

Miller: You see it scattered through the city.

Caldwell: How do you see this sculpture in relation to your previous sculpture work? More specifically, with the temple in Portugal and the prayer wheels and the tiles in Brooklyn?

McNeil: I think it’s kind of part of the same language. We’d been working with Charlie Becker on all of our sculptures for the last ten years, so there’s that kind of thread that ties all the work together.

Miller: Some are more simple, like the “Bunny Boy” sculpture or the “Scuba Horse” sculpture, which are really just a sculpture of an image and you know that image has sort of got it’s own things that go along with it, whereas the temple was much more of a full scale installation. Things like the Deluxx Fluxx arcade were much more about taking over a space and creating an environment and creating a bigger story through all these different smaller images.

McNeil: I’d say there’s also a slight tweak to the sculpture in the sense that Bat Munkh, the guy who we worked on it with out there, sculpted it and it’s got some accents of his flavor in it, whether that’s how he treated the surface or maybe some cross-hatching techniques, where the original that we did was more smooth on the jacket. Just some slight shifts. You know, he comes from Soviet sculpture training, so you can still see some of those like communist kind of style line work in the jacket and there’s kind of a strange rigidity and boxiness to it.

Caldwell: So you did a little bit of street art while you were in Mongolia.

Miller: We did. So when we went out originally, we were planning to do a small mural along with Mongolian artists. We brought along some of our stencils just to kind of go out and explore the city a little bit with.

McNeil: Yeah, we kind of went out with one major idea: A collaborative thing with some local artists and then the rest of the stuff was more like tinkering. I wish we had more material there to go and be a little more aggressive out there.

Caldwell: Can you tell us about the mural that was organized with Mongolian artists?

Miller: So it was in this long hall. The image was this girl sort of set in the Gobi desert holding a skateboard. When we got out there we had really fallen in love with just like the texture of the background on some of that stuff. So it was just a simple image of this girl in the desert, longing to skate. We just did these 8 and then all these Mongolian artists basically did all the dresses and painted those in. It was sort of a fun, simple, collaborative piece. You don’t see a ton of street art going through.

Miller: I think the biggest surprise for us was going out on our own and experiencing the way the locals really embraced street art. They’d see the sort of stencils we had and they’d be like “Oh, I really want that on the front of my building!” The wolf images really spoke in a powerful way to them and it’s such a strong character in our work. I mean, it’s rare that you get the opportunity of someone saying “Oh, will you please put that on my building or on my house,” or whatever, rather than being chased away. That was just a really great experience.

They were really warm, open and interested, and we found that throughout the people there. I think that was certainly the biggest highlight of the trip, was just the people and getting to know them and just how much they seemed interested in everything. The city itself is just coming out of this industrialized phase and quickly developing into a modern city, and it’s not the prettiest city yet for these kinds of things.

McNeil: But it’s got the idea of promise and possibility.

Miller: It was just great in so many ways to get out there and experience it.

McNeil: There were so many spots too. It takes awhile to get settled in with jet lag and all that stuff. Then when we got settled in we were just like “I wish we even brought more stuff to do.” But the other thing, too, was that it’s really tough to get good spray paint out there. The stuff that we did have, we had to do so many coats of it and it was just such crap.

McNeil: This one guy was fascinating: 75 years old, walked up and was inquiring, like “What is this? What type of art is this? What do you call that? I really like it! I’m really fascinated. I’d love to write an article about it! I’m a journalist for the newspaper.”

C: Was there anything about this trip that really spoke to you enough to inspire future work?

McNeil: The Buddhist temple that we went to was pretty inspiring. That was the first time we got a chance to spin actual Tibetan prayer wheels and that was really fascinating, seeing how many different types of prayer wheels there were; like ones that were made from metal, ones that were made from wood, ones that were fabricated from like old oil drums or put together with nails or aircraft rivets. Some were welded out of sheets of brass or copper.

Miller: There’s a massive sculpture inside of what really didn’t look like a big building, and then you get in there and it’s just this statue. It’s huge, it’s pretty wild and the building is filled with all these little Buddhas and prayer wheels and it was really really great.

Caldwell: What was done for the unveiling of the sculpture?

McNeil: They played traditional horse fiddle and there was Mongolian throat singing. It’s really crazy, they produce a really low, deep tone, with their voice along with the violin, and at the same time they’re producing a second tone that sounds like a whistle, so they’re producing two tones at the same time out of their mouth, with a fiddle.

Miller: It was pretty amazing. At the unveiling, people from the national park spoke, the Mongolian Arts Council, and people associated with the project.

Miller: Yeah so in that sense it was really great. It was just an amazing trip all around. I think one thing we kind of talked about at the end was just that, you know, so much of our work is based on being temporary. Doing street art you know that you’re gonna go and it’s gonna be gone someday, or changing constantly. So it’s really interesting to do the work of art that is staying permanent and the city is changing around it.

McNeil: Yeah, that’s probably why, going back to your question about ‘How is the sculpture different?’ it’s that it’s permanent. This is first one that we’ve done that’s been like a permanent piece. When people go back there like in 10 or 20 years, it’ll still be there.

Photos courtesy of Faile