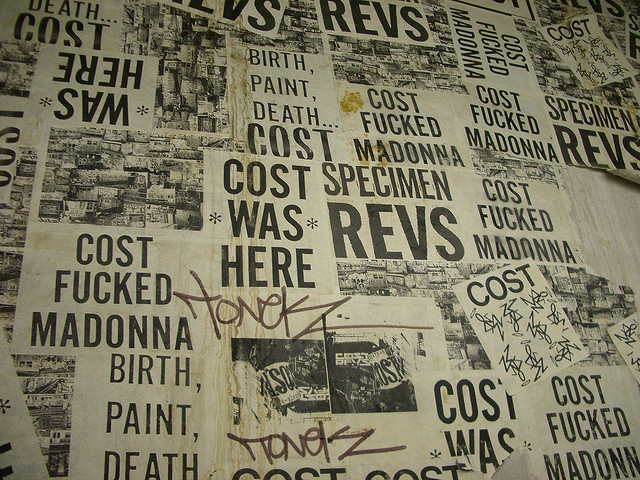

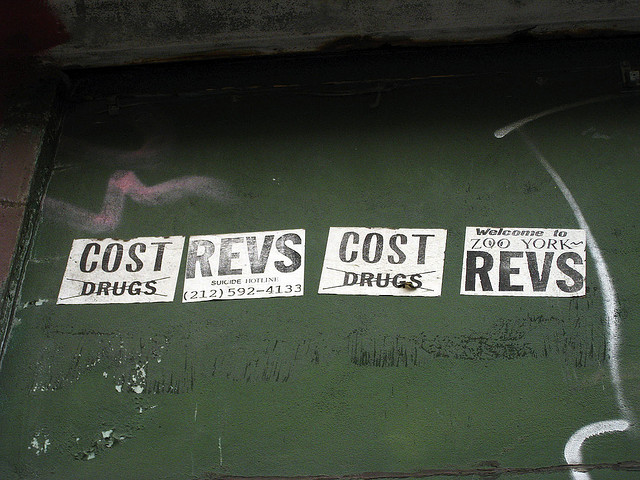

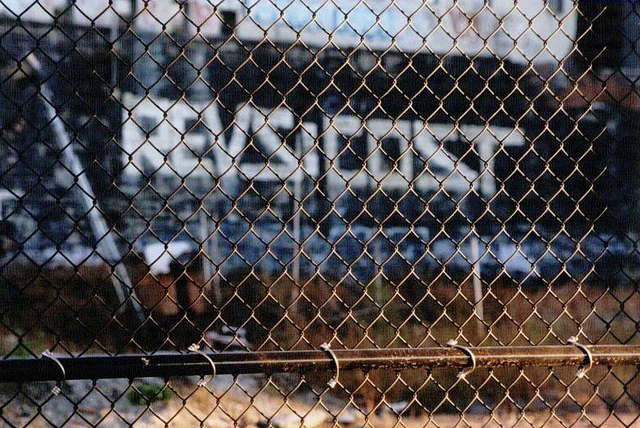

You know him. Rudy Giuliani knows him. At one point, half of the city thought Madonna knew him biblically (for more on that subject, hold your breath for Part two). COST has been ubiquitous in New York City since the late 80’s. He and his counterpart REVS are two of the most widely recognized characters in graffiti and have produced some of the longest running pieces in New York. Nothing captured COST and REVS’ domination of New York in the 90’s better than this Videograff video which asks “Is this art or dangerous propaganda?”

After working under the radar for a number of years after his 1994 arrest, COST has participated in a select few projects with brands such as Brooklynite, Showpaper and Supreme since the fall of 2010. Within the last few months, you may have seen the name COST appearing around New York City again. Despite this, he’s let the work speak for itself and shied away from the spotlight. Vandalog is pleased to publish the first major interview with this reclusive graffiti legend since his 1994 interview with Art Forum. In part one of this interview, COST discusses getting arrested, his hiatus that followed, doing graffiti against the grain and his resurgence among the latest generation of street artists.

V: Why haven’t you tried to make yourself a presence on the internet?

COST: I stay off the internet. The internet is like poison. It really is. I don’t want my face on the internet. There’s a lot of misinterpretation. Anyone can be anyone, say anything. On Facebook there are two people who are posing as me. Things like that make me, I guess, bitter toward the internet.

It’s a good way to connect, that’s true. But I think true graffiti artists have a disconnect with a lot of things in this world. At least I do. I stay disconnected- try to stay disconnected from a lot of stuff and that’s part of why I try to stay off the internet as much as I can. I mean, I’m on a little bit, but there are people out there creating a whole graffiti world on the internet; websites and storylines, bios, all that. They’re selling themselves on the internet and I don’t want to do that.

V: During your wheatpasting campaign the posters that had a phone number received a lot of attention. To be general, why did you do this? And do you think that was the 1993 version of putting, say, “www.COST.com” up like graffiti artists are frequently doing today?

COST: During that time period nobody was doing it. That was a way for the public to contact us. You know, get a little feedback on the shenanigans we pulled around the city. We were having fun, trying to keep it pure and doing what we wanted to do if it felt right at the time and hopefully – maybe not now, but then it was a different thing than what everybody was doing. We were speaking out to the public. So the phone number was kind of like an opportunity for the public to respond or reach back to us and say things. And they had a lot to say.

V: I mean, it is kind of intimidating to see a phone number on a wheatpaste. You don’t know why or why not to call it, or what to be ready for. I dialed it but got nothing.

COST: Well it’s nothing now, but we used to change it up about once a week. Rudy Giuliani was the mayor and he was trying to clean up New York, and obviously if you look around New York now it’s a different town. He cleaned it up. But on the voicemail we went on political rants, spoke about art, philosophy, whatever was on our minds. We spit it out onto the voicemail and it was freedom of speech. That was the beauty of it. We were saying what we wanted, when we wanted and anyone could dial in – for what? ten cents? – Whatever a payphone cost at the time. You never knew what you were gonna hear on it. If I had a bitter day and I was a bitter guy that day and I had something to say about it, I would say it. We didn’t hold back. We said what we felt and what was true to us, REVS and myself. Initially a few people called and before you knew it, thousands of people were calling a day. It kind of got a little out of hand. Checking in on the voicemail, we got everything from death threats to marriage proposals to people telling us to just get a life.

V: What did you think of that?

COST: Some of it was inspiring. Some of it was… some of it would make us go out and do more, you know? It added fuel to the fire. We were young, in our mid twenties – a very rebellious age. I’m 43 now, you get older and mellow out a little bit. We were young and rebellious so we wanted to vent and to tell the city that we didn’t like how it was being run and wanted to switch it up a little bit. We wanted to mix things up, add a little flavor, switch things around. I’m glad people recognize that now.

The funny thing is that now that there’s an international street art boom, it’s like people are remembering it a little more, but at the time it was almost looked down upon. During that time period a lot of people didn’t like what we were doing. They didn’t consider it art because it was very um… neanderthal.

Graffiti at one point got so perfect where everybody was doing perfect lines and the art was so over-perfected. If somebody did a perfect line, we painted a drippy line that dripped everywhere.

V: Intentionally?

COST: Yeah. We were doing everything against the grain. We just went against the grain of every graffiti and street art standard of the time. A lot of people were very angry that we were prolific. We were out there every night almost. I would say we were putting pressure on the graffiti scene and the street art scene to question what we were doing. And some of them were upset, you know? Because we were changing the rulebook. I don’t know if we were trying to, we were just doing what felt right. Now there’s a whole new rulebook and now people look back say (I’m not here to toot my own horn) but they say “Oh, you guys did good things and helped influence all the street artists now.” And I’ll take it as a compliment.

V: What kept bringing you back? Every night you kept doing this. What was attractive to you about it?

COST: I can speak for REVS on this as well: Neither of us did graffiti for the love of graffiti. It was more like we actually didn’t like it. We probably hated it. It was just self-expression and it was pure. We were just pouring our heart and soul into the streets, and people can take it or leave it. A lot of people didn’t appreciate it then. But now a lot of people look back and -you’re interviewing me so at least Vandalog, or somebody, recognizes that what we meant was true. I hope you can print that. What we did was true, was being true to ourselves. I’m not sure all the street artists are being true to themselves. They see one mural and someone does a mural just like it. I don’t mean to be critical, there are a lot of talented artists out there. Much more talented than me. But do they have something to say? And that’s really what I question. When I look at art, it has to speak to me. If it doesn’t speak to me than what is it? A beautiful portrait? If you said, “Paint me a portrait,” our waitress will paint a better portrait of you than I can. You know what I mean? It’s about the art. The art needs to speak to you, it needs to move you.

V: How did the release of your identity after you were arrested affect your personal life as well as your graffiti life, which had before been separate?

COST: It made me go deeper undercover I guess. I crawled into a shell and laid lower than the outlaw Jessie James. All of a sudden people who didn’t know that that was me put two and two together. You don’t want people knowing who you are. The idea was to do graffiti, and the idea behind graffiti was to get your name out there but for others to wonder who the heck was doing it. I never did it for a social purpose. Or a financial purpose. I did graffiti for myself and my cohorts and my crew and that was about it. And once my name got out there, it was exploitation in a sense. That’s how I looked at it. It was pretty harmful. But now that the street art/graffiti culture is so accepted, there’s been less hate and more embrace. So I’m not complaining.

COST: After I got caught it just derailed me, like a train. I just went right off track and I got into other things in my life. I was getting a little older, I was in my late twenties. I got into different ventures. I found some success in other areas of my life. I’m trying to figure out how to explain this properly.

It was like I was pushed out of graffiti and street art out by Giuliani and the city with this punishment. They put the cuffs on me and when I was free to roam, I still felt like I had the cuffs on me all the time. I had to make a living so I started a business and I guess I got somewhat successful and I realized that there’s no money in art anyway. There are a few people who make a lot of money off art and then there are the rest; it’s like a pool, a starving pool chasing that dollar. That’s what it seemed like to me. So I got successful in other areas of my life with business and the more successful I got, the more street art and graffiti got away from me. I have my regrets about that because everything I did was very unfulfilling, but I was earning a good living. It left a very empty feeling within because I wasn’t doing what I really wanted to do.

V: Had you done any painting at all during that time?

COST: For the first 5 years after being arrested, I was on hiatus. After that, I painted off and on but it subsided. It felt like I lost my way, like they pushed me out. It’s almost like you choose paths in this life and I wound up going down a different path, and now I really regret it. I feel like I only have about 20 or 25 years to live, I figure 65 years old, anything past that is a blessing. People live longer, but you know what I mean. So I figure with 25 years left to live, anything that I’ve done up to this point since my heavy street art days have been so unfulfilling that I’m going back to street art. I’m willing to sacrifice everything in my life otherwise, at this point. That’s why I’m going back to painting and producing work, because all the money in the world doesn’t give you uh…. what’s the word.. I forgot the word. Shit. You gotta do what feels right in this world and I gotta get back to my painting.

V: How does it feel knowing that for 15 years there was a time where you weren’t doing anything in that scene and people were still talking about you?

COST: Well, I didn’t really take a complete break. After that rift, I painted trains, moved into street art and have kept going ‘til now. It’s going on 30 years of graffiti. Of course, there have been different time periods where I was going heavy and light and stopped. But I never really truly stopped. Even when I stopped for different portions and got into other ventures in my life, I still made comebacks.

V: So you actually had been painting throughout the duration of that supposed break?

I don’t want to toot my own horn here, but in 2005 I didn’t do street art, I just did graffiti. And I went all-city and every writer in town knows that.

V: Under the same name?

COST: CO. Just CO. I took CO tags, just my tags with spray paint. I did the whole city. Every graffiti writer worth his weight will tell you “Yeah, he went all city in 2005.” And it wasn’t like I was trying to make a statement, except to the writers. I was just talking to the writers. I was just telling the graffiti guys “Guys, I’m still around.” That was all. I’m still around and at any given time boom, I can take over. And that sounds arrogant and pompous, I know, but for two months straight I was doing graffiti every night until I got bronchitis. I wore myself out every night on the streets until I got bronchitis in the lungs and had to stop, but I would have gone out for almost another month. I wanted to put up about 10,000 tags but I did 8,000. I never got to 10. But I just wanted the graffiti guys who said “Oh, Cost is washed up” to say “Oh, he isn’t so washed up” and boom, I did it just like that. It wasn’t like a big thing for the street art world with murals and going international. But all the New York guys, the true New York guys, know that in ’05 I made a comeback. So I always do come back, and I’m due for another comeback anyway. I always come back every few years. I never really disappear, but, you know, it’s not like I’m gonna tell this to Bloomberg or Giuliani. It runs through the blood. It never goes away. I’ll write ’til I die.

V: What was your first piece after you got caught and were arrested?

COST: Oh, God… It had to be after I got caught. I did a canvas entitled “Derailed”, which shows a train derailing off a track with a skull coming off the front of the train and going on to the track. Looking back, it probably had something to do with what happened to me when they knocked me off my mission.

There was so much left for us to do when I got caught. We had been caught a lot of times, but that trial got me to the point where I had to stop. We knew we were going to get caught. If you write graffiti a lot and you’re very good, even if you’re 99.99% careful, there’s still that .01% you’re going to get caught. So eventually you are going to get caught. If you write a thousand tags and you got away with 999, you did well. But that one time a cop saw you…

We were good, but occasionally we got caught. It catches up with you. You can’t get away with it forever. Neither can a serial killer. These serial killers all get caught. We got caught a few times. But it happens.

V: What did you think of your punishment? They had you cleaning up other people’s graffiti, right?

COST: I don’t know. Now it’s a felony. When I was a kid, they would slap you. When I was a kid in the train yard, they’d write on you; they’d write on your face or write on your shoes and slap you around and tell you to get out of there.

V: The police? Oh my god.

COST: This was the 80’s. If the cops brought you to the police station for graffiti in the mid-80’s, the other officers would laugh at the arresting officer for bringing you in. It was called a “bad collar.” The officers would poke fun at the arresting officer saying, “This is what you arrested? There’s people killing people. There’s people pumping crack into their veins. There’s people breaking into stores. Robbing, stealing, and raping, and you arrested a little kid who wrote graffiti who’s like 14 years old?” It’s like, “What is that?” So they’d laugh at him. Nowadays, it’s a felony, and if you make a graffiti arrest, it’s considered a very good thing.

V: Did that have any part in how you guys were able to get up so much?

COST: In the 90’s when we were getting up a lot, the trains stopped so graffiti came to the streets. It became a free-for-all. The cops weren’t really aware of how graffiti artists were approaching their attack of the streets, so the streets were there for taking and we just went hog wild. Now the cops know what to look for and if they see you they arrest you and put you through central booking; it’s a felony. Back then it was a misdemeanor; it was joke. Sometimes you’d get a little desk appearance ticket. You were in and out, had to pay a little fine, do a little community service. Now you go to jail, you go through the whole system, you see a judge. So the penalties have changed. You can get in real trouble.

V: What do you think about how the penalties have become more severe?

COST: As I’m getting older it makes me not want to go through that experience again. I’ve gone through those experiences a lot and I don’t want to relive it. You wise up as you get older. I’m a little less rebellious than I was in my 20’s. Central booking is no fun. That’s a good quote. Central booking is no fun! An old cheese sandwich….. and uh… central booking is no fun!

V: What initially brought you to graffiti and street art?

COST: I guess I’d say family issues, a lot of free time on my hands, wanting to explore, moving to Manhattan. The city was a shithole at the time and everywhere you looked the trains were dirty and graffiti caught my eye.

V: Any specific artists influence you?

COST: Back then, a guy named ZEPHYR. He was my biggest influence on handstyles at the time.

V: What is the importance of documentation to you?

COST: Oh *laughs* not that important. I don’t do too much documentation of my stuff. I do the graffiti and I leave the documentation to the documentors. I used to document all my stuff in the earlier years. But since documentation has become such a way of life for like street and graffiti art, I don’t document anything anymore and I just let people do the documentation on their own and whatever pops up, pops up. Whatever gets pushed to the wayside and is lost in the shuffle is fine by me. I kind of just wing it and let people document as they wish. And if it appears on a website or like Instagram, then it’s there. But if it’s not, then it’s lost in the shuffle forever, I guess.

V: You sit in the sort of gray-zone between graffiti and street art. Where do you see yourself and is that even important to you?

COST: In my world everything is black and white and that’s not a good thing to most people. It’s interesting you ask that because people have told me we’ve actually bridged the gap between graffiti and street art. Cause REVS and I, we’re both graffiti writers. We’re graffiti guys. We wrote on the subway cars in the early 80’s and painted, and the new guys don’t do that. The new guys do street art. So we actually did graffiti and we did our fair share of that stuff and then we crossed over to street art. Some people have said that we bridged the gap.

V: You’re known for being quite private. But then you did that piece, the newspaper box, a few years ago for Showpaper which was later shown at Art in the Streets. How did all of that come about?

COST: It was just on a whim. A good friend of mine named Ellis Gallagher, who does the shadow outlines on the street, and the curator, Andrew Shirley, contacted me and said “Hey, do you want to be involved?” I was at a point where I was saying “No” to everything in my life and I just said “Yeah!” It went from no to yes overnight, I don’t know what happened. It was a great experience on a lot of levels, getting involved in something positive like that. It was still illegal, but there were a lot of positive aspects to it. Since then I’ve come to realize, “Hey, graffiti, street art, why not embrace it a little more than I have in the past?” I don’t need to be an urban cowboy for the rest of my life. At my age, an urban cowboy is not the answer. You got to switch it up at some point, you know?

V: And then you did the snub-nose print series with Brooklynite Gallery.

COST: Same thing. That happened around the time I did work for Showpaper, Supreme, and the Faile prints. All around the same time I just said, “Yes, why not?” You know? “Go for it,” I said to myself. I just wanted to jump back in the game a little bit; let people know I wasn’t dead yet. And now, I said I wasn’t going to do graffiti until September. I was going to spend the next couple months sort of in the lab, feeling out where I want to go and in what direction, and in the last month or so my direction has just sort of taken shape and I’ve just been going with the flow more and I find I’m living the lifestyle again.

V: There’s a rumor that you coined the phrase “The gentrified graffiti-street art generation.” What does that mean?

COST: *Laughs* Yeah. I was talking with a friend about the old school, the new school, the pioneers and everything in between, and I started to realize that all the new street art being produced is what I would label “the gentrified graffiti / street art generation” because the city, and ll the bad neighborhoods with in it have been gentrified. It’s become such a commonly used word in our culture that it should really be used in the graffiti subculture as well. I think it’s a good way of describing the new generation of graff-guys. They don’t have the same approach that the old school guys do. The old school guys are much more gang and crew oriented and it was all about you and your crew, and there was a certain structure to graffiti. The “gentrified graffiti generation” seems to have more of a frolicking, laid back, fun approach to graffiti. When I was doing graffiti as a youth, it was much more hardcore. Well, the city was more hardcore. It was hard-living going on in New York and that was expressed by the youth through their graffiti. The city has been changed and so has the graffiti scene. Thus, you get the gentrified graffiti-street art generation.

Photos by elswatchoboracho, Luna Park, Press Pause, Shoehorn99 and Sizzled