… is in europe be on the lookout.

Photo by buddz909

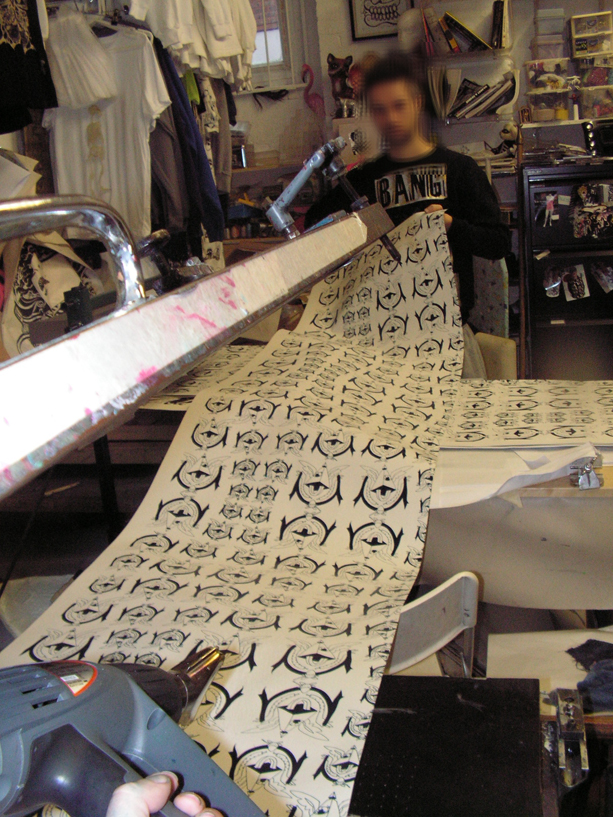

On a hot summer’s day, about a year ago, I headed to High Roller Society for the second in a series of three workshops on the art of printing. I was particularly excited as this session covered the subject of screenprinting, a technique I actually knew little about. For me screenprinting was nothing new, in fact for anyone with an interest in art, let alone street art, it should be nothing new. But I will openly admit my knowledge on the process behind it was lacking.

Whilst I was eagerly anticipating the workshop itself, I was equally interested in meeting printermaker extraordinaire, Aida. Starting out from her mum’s bath, which she claims she ruined, Aida began producing her own clothes over a decade ago. Now running her own successful brand, Brag Clothing, alongside lecturing at the London College of Communication, Aida is perhaps equally famous for her work with some of the UK’s leading street artists. A list that includes the likes of Lucas Price, Sweet Toof, Sickboy and Kid Acne among others.

Surrounded by tables of printing equipment including her trusted squeegee, Aida began the workshop in earnest. Her passion and extensive knowledge kept the audience captivated from the first minute whilst she covered everything from producing screens and mixing inks to actually getting hands on, with everyone having the opportunity to pull their own print. It was a thoroughly enjoyable afternoon and I now view screenprinting in a completely different light. The skill, attention to detail, and creativity needed to be successful is amazing.

Following the workshop I was eager to catch up with Aida again and discuss screenprinting further, including its relationship to street art. It may have taken me a year but it was definitely worth it. Not only is Aida’s studio an Aladdin’s cave of printed wonders but it was refreshing to sit down and hear her opinion on a variety of subjects. I often think that the process of screenprinting and the printer themselves are forgotten, you may have a wall of prints yourself but have you ever thought about what goes into producing them? Hopefully this interview goes some way to answering that and you find it as interesting as I do.

Shower: How did you did you get into screenprinting?

Aida: I got into screen printing when I was about 18. I had seen it done before and at the time my work was quite photographic. And I liked the fact you could make multiples of something and change it.

But I suppose it depends who you are though. Most people that I know that have got into screen printing, are people who enjoy some sort of learning through process, and most produce work that actually lends itself this method of printing. However the people I know who are successful at screen printing were screen printers first and became an artist second.

How did you get involved in street art and the artists who you work with?

I actually didn’t know anything about street art up until about 3 or 4 years ago. I had my shop in Brick Lane and I just made clothes in my workshop downstairs. I just loved printing and I used to make loads of stuff – clothes, prints, canvas’s, and obviously being in Brick Lane I used to get loads of street artists hanging around. It is a great place to showcase work, it’s amazing.

The little street I was on was covered in quite a bit of graffiti and the artists used to come to the shop. I didn’t know these people whatsoever; it was just bizarre that they used to just approach me. I first got approached by a few to paint next to my shop, I didn’t know who they were so I researched them a little bit and reluctantly let them do it.

So I suppose I just got into it that way, and next thing you know, I had people like Kid Acne coming in and saying “Oh your clothes are really cool, did you print these? The colours are so good. I want you to do a print.” You just got a phone call here and there and that was it. To be honest, I still don’t know a lot of people in street art, it’s mainly just the people I work with.

So a lot of it was through word of mouth?

Yeah, word of mouth. And through the clothes and through the quality of the print. I think it’s a relationship really between myself and the artist.

Can you explain to me a little about that relationship? How do you take an original and produce a print?

It depends who you work with. For example, for a project like Safewalls, both Glenn [Anderson] and Sweet Toof wanted a full reproduction of the work. Due to the amount of colours I opted to cross between spot colours like flat colours and process which is CMYK – cyan, magenta, yellow and black.

If you haven’t been printing for a while it’s a really difficult process to do because you have different varying sizes of dots, inks are mixed, and I like to mix mine from scratch so I can control the amount of CMYK in relation to each other. That’s one way.

At other times, a lot of other people I’ve worked with like to come into the studio and draw directly onto drafting film. You have two light fast pens and they draw sporadically, often improvising. But personally, I think the best way and the most successful prints that we have done are the ones where the artist has worked directly, hand drawing work that is transferred directly onto the screens.

Why do you think street art takes so well to the screen printing process?

Screenprinting is a process that allows you to get multiples out of things, but it’s also about documenting. Street art doesn’t last for too long on the street so the best way to capture it before it gets buffed, while a canvas may take a long time, is to screenprint. It’s really is documenting it.

In addition, there is a trend at the moment where everyone thinks “Oh yeah lets put out a print, it’s going to be an instant hit, it’s going to sell out!” But, in reality, no it’s not! A good print isn’t about copying what’s on the street to make an instant hit. You just have to go into some print house or gallery, and you’ll see loads of editions just left over, that have cost thousands to make. It’s a silly way of thinking.

I just think you have to understand that not every single piece of work lends itself to being a screenprint. In fact, when I was talking to Glenn [Anderson], he said, for his work that’s so detailed with so many colours, he would like to start thinking like a screenprinter and how images can be broken down and simplified, almost like when you are trying to create stencils but with a lot more detail.

But an important point to consider is that most screenprinters would say that screenprinting isn’t a process that is for a full scale, full colour reproduction. It doesn’t lend itself to that. If you want that, you go to do a digital Giclee or opt for a more traditional process like Lithography. For me screen-printing is an interpretation of someone’s work and not a full scale photographic reproduction.

So it’s almost an art form within itself?

In the hands of a professional printer, yes, it can be an art form. It takes so long to get the colour balance right, the right separations and screen mesh, even the way you set up the hand bench contributes to the quality of the print. To actually produce 70 prints that you don’t have a finger mark on, especially when the paper has been in and out of the drying rack about 10 times – printing, drying, letting the paper breath, cutting it to size, it’s a long process. A real labour of love.

On the subject of some people turning to screenprinting with the aim of becoming an ‘instant hit’, I wanted to ask if would ever work with artists with that frame of mind?

Personally, I’m in a really comfortable, happy situation, where I only work with people who I want to and respect. That’s why I’m an independent printer, that’s my ethos, work with people who know about the process, who are true and can actually draw or paint.

You know, you can approach any print house though and they will knock anything out for you. I don’t think there is anything wrong with being an entrepreneur and using initiative to make money. But at the end of the day it’s the respect and the longevity that they probably won’t have. So you know, yeah a quick buck is good but your reputation is going to suffer or bring any longevity for your career as an artist.

You say you only tend to print for people you know or like, but do you ever end up printing pieces that you don’t personally like even though you like the artist?

[With a smile] I have done in the past, yep, quite a lot, you call it your “bread & butter” jobs, we all have to pay the rent! There are some people who really want me to do their stuff and I’ll have a time slot and I’ll think “Why not? Let’s do it.” But I might not gel with them, you know. Don’t get me wrong, there are times when I’ve done a print and they aren’t happy with it, it hasn’t looked the way they want it to. But that happens.

But on the whole they are happy?

Of course, most of the time they are happy. But you know what, I hate to say this, but when I’m printing something, I know fairly straight away if it’s going to sell or not. But my clients never ask me that, most just want to see the finished print. Although if I am close with the artist I do offer my professional opinion sometimes.

Is that based simply on aesthetic value or as a printer do you possess a more in depth understanding view?

I’ve had my own business for over 7 years. I started on various market stalls, grafting in the cold, and for 3 years did a lot of market research watching people’s faces and hearing the comments. So I kind of more or less know. That’s why when I release a print myself, I wait and wait and time it. I time it commercially. I more of less know when to release things, colours etc. I’ve got good experience in selling.

What impact do you think screenprinting has had on the street art movement and its commercialisation?

I think in the last 2 years, it’s played a really big part in the street art movement. For example Eine’s 70-odd colour print had a really big impact. It showed the versatility of screenprinting. I love the way you can take away a colour, bring a colour in, take some off the rack and just play around.

I don’t know whether you could call it kind of selling out for the street artist but I’m still toying with the idea of this fast buck and making a quick profit. In general, I still go back to thinking street art doesn’t last. I still think, for the pure people, it’s about documenting.

But I do know some street artists that are real craftsmen and craftswomen, who do their own print making and screenprinting. And I think if they do it themselves it’s a really good form of expression. However then you have people like POW that mostly release street artist’s prints and they have made a really huge business out of it. So I suppose they have had a really big impact on street art, they are the foremost forerunners in the market in my opinion.

So having a print with POW sort of means you have made it? It’s kind of a big deal.

It’s a really big deal, I would say a privilege to even be asked! The impact of POW in the screenprinting world for street art is huge.

But, the question is, what do you do after you have had a print with POW?! That’s the thing about screenprinting, its about producing multiples, it is so easy to get carried away and make so much art, flooding the market and having your prints left on the shelf. It’s such a sad thing when you look at a big stack of prints and realise only 30 per cent of the edition have sold, does this affect the collector who only buys a print as an investments?

So maybe the way forward with making street art prints is to make small editions, with a bit of hand finishing. But still, I think that a print should be affordable as that is why any type of print process was born to be. I think artists thinking of producing prints should remember this, unless they are a screen printing artist and only produce work in this medium. If you can’t afford to buy an original work of the artist that you like, you should be able to afford a screen print by them.

With regard your input, how much of a contribution do you have in the prints that you produce? Does this change if an artist just sends you a Jpeg?

If someone does actually send me a Jpeg or something, I’ve actually got a little disclaimer. I advise on the basics that a lot of people might not have had any experience of printing. I try to make it kind of friendly and put in layman’s terms of what you can get away with and what you can’t, the size of the image, shrinking it down and that kind of thing.

Sometimes I do get an image that just won’t be conducive to the screenprinting process. I have some impact in telling them to change it, but in those aspects the artist tends not to much. They tend to say just do this and that, end of.

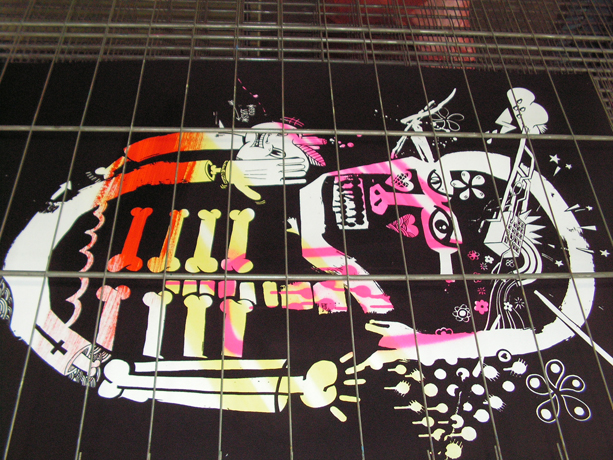

But then, if I’m working with the artist in my studio and they just come in and do something, they do often ask me about colour, about size. When I was working with Nychos for his solo show for Pure Evil, I think we sat down for a couple of hours and discussed which image would work on what size paper, and then we discussed colour for about 2 hours with my little Pantone book. Whereas with someone like Lucas Price, we sometime improvise which is quite nice, we just try things out.

With the Safewalls project, I don’t think I’ve ever had this much creative input in doing something. I think they trusted me to do the best I could. I was given the images from the originals and told you can basically do what you want as long as you make it look really good. But then you get some artists, even down the phone, who say; “Just choose a green, pistachio green, that will do!” And your like “what do you do?!”

That’s a lot of faith in you!

Yeah, it’s a lot of faith. But that again is the core thing about what I believe – everyone should have a really good relationship with their screenprinter. It has to be a really tight relationship based on trust.

You work so closely to the artists but how do you feel about credit and credit for a print?

It’s fine. I’m just their printer.

Really?

I have no attachment. Nothing. I know, I’ve spoken to other printers that are artists as well, and they are always like “Well you know, your hand was in making it.” Sometimes an artist might just give me just a line drawing and I have to sit there physically by hand, because they might not use a computer, and a lot don’t, tracing and doing stuff on drafting film. I’ve more or less made it, I’ve separated the colours, I’ve tweaked it, and I’ve mixed the colours.

You really are the artist behind the artist then!

Sometimes, sometimes you are. But you know what; it’s not your work. You didn’t conceptualise it or draw it, you didn’t think of it.

But you produced it.

I produced it, like music producers do, but it’s the singer who gets the credit! And I enjoy producing work for people. I like the look on their faces when they see the finished work. And usually they will recommend me to other people. That’s my reward, it’s nice. I just like to help people out.

But to be honest, If I wasn’t doing my own art too it would be different. I think I would be quite frustrated. I know a lot of printers that are just in a print house from 9-8 or whatever, who are just printing other peoples work and it gets you down.

You have obviously worked with many successful artists, but what would you say is your biggest achievement?

This is going to sound stupid, but when I was 19 or 20, I always had an idea of what I wanted to do and I always knew I would work for myself as I was such a control freak. And when I was about 21 or 22, when I was graduating, I wrote a little manifesto about keeping it real and being true to one’s self – lots of arrogant views on mass consumerism, and you know, creating something niche but something that I was always going to make a living out of. At the end of the day why do you work? Or why do you believe in your craft and want to better yourself?

It’s to be successful, make your family proud, and if you can make a living out of it, that’s a bonus. And I think that’s my biggest achievement, that’s what I’m proud of. Going back to my core beliefs, I’ve tried to maintain this. I’ve met some of the best, most talented, hard working people in the world and I’ll be meeting loads more, I hope. I’m still making a nice living by doing what I’ve always set out to do.

That doesn’t sound stupid, just pretty grounded and level headed. One final question, who are you inspired by and why?

I’m inspired by all the people I meet and work with every day. Every different person I meet brings a new thing to the table. Like when I met Glenn [Anderson], I thought “Wow.” You look at his pieces, you look at his detail and you think “How do you do that?!” Or you take little Nychos and you look at his walls and again you just think “Wow.” I’m amazed by everyone I meet everyday.

If you would like to know more about Aida, or check out Brag Clothing, then head over to the newly refurbished Aida Prints website. And if she runs another workshop then I highly recommend heading along, but in the meantime you can read up about last years High Roller event thanks to a great review by NoLionsInEngland over on Graffoto Blog.

Photos by Aida, High Roller Society and Shower.

There are a couple new collaborations involving Sweet Toof to share today. Two with American writer Smells and one with Paul Insect. I’ve got to say, Smells has to be one the best writing names there is. Also Screw. That’s a good one as well. Because they work so well in tandem with other writers. Anyway, here’s the work:

And while I’m on the topic of an artist that some people think I blog about a bit too much, I might as well mention that occasional Sweet Toof collaborator Malarky has been very busy lately.

Photos by Alex Ellison

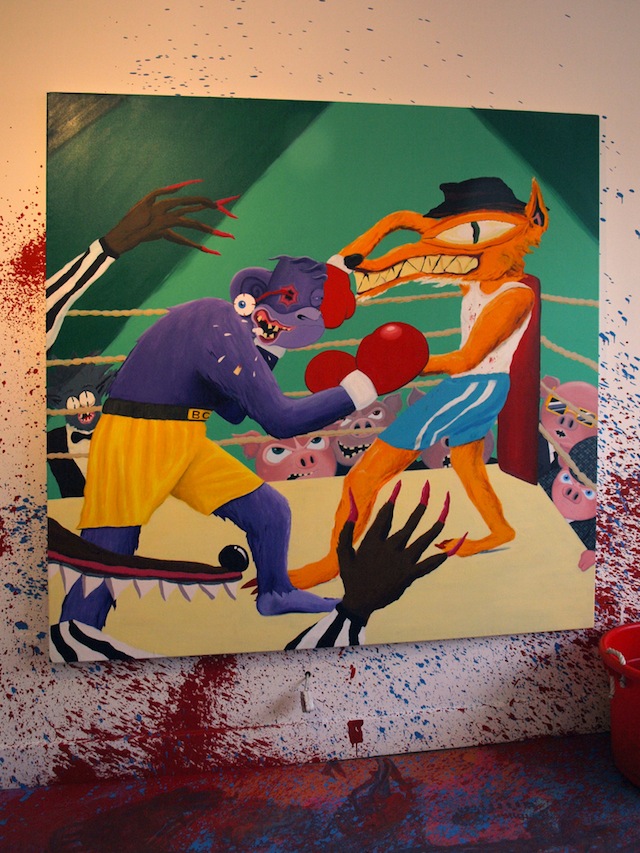

Burning Candy have a show, A Fist Full of Paint, on right now at Tony’s Gallery in London. There’s work by Rowdy, LL Brainwashed, Sweet Toof, Dscreet and Mighty Mo. For the most part, it’s the sort of show you’d expect from Burning Candy. I’m a fan of the crew, so I enjoyed it. But most of the work wasn’t going to convert any new fans. The possible exception to that are the pieces by Mighty Mo. He has continued to develop his style of making realistic models of his outdoor work. These pieces were what everyone at the show was talking about, and they were as fun as ever. In fact, I think Mighty Mo is getting even better.

While Steph can go on about Morley all day long, Mighty Mo an artist who is actually finding an interesting way to transition from the street to the gallery. Like pieces by Invader, many of Mo’s sculptures depict actual street pieces, so the work acts as a sort of nostalgia trigger and documentation/preservation of outdoor pieces. At the same time, there’s a high level of craftsmanship.

And Mighty Mo can paint well on more traditional canvas as well. Check out this collaboration with Rowdy. It’s a knock-out… (yep, had to say it)

S.Butterfly has more photos from the show on her flickr, and if you’re curious about all the paint splatter on the walls of the gallery, watch this video.

Photos by S.Butterfly and Alex Ellison

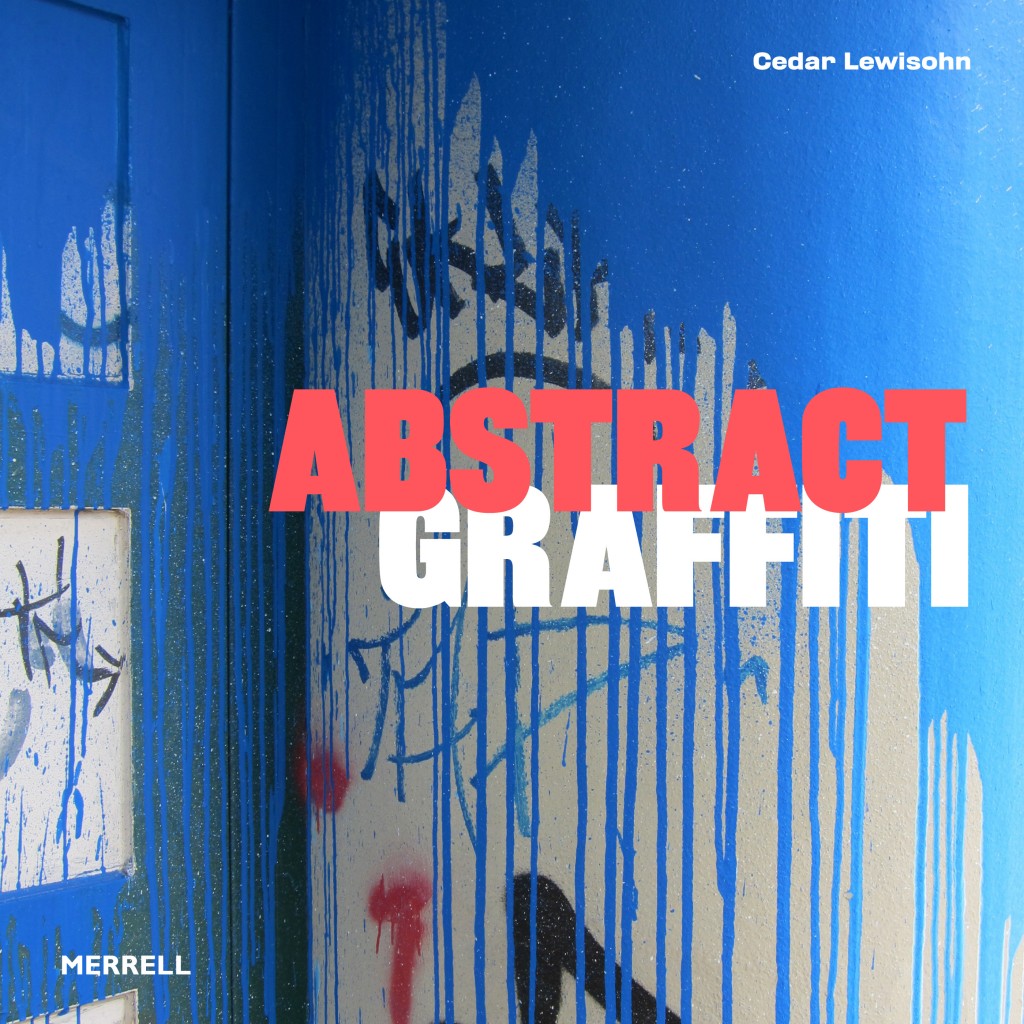

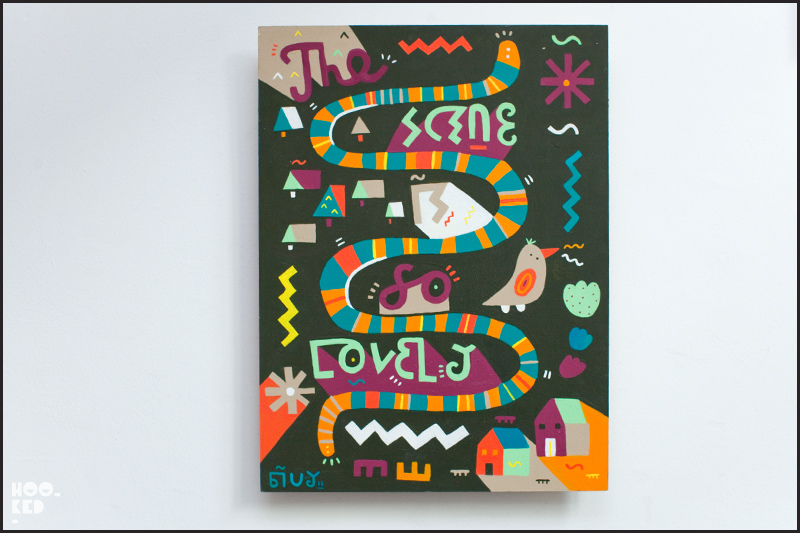

Often I find myself asking why certain artists have not been included in a book, but when it comes to Abstract Graffiti by Cedar Lewisohn, the spotlight is not on who should have been showcased but who has been and what they offer.

This insightful, thought provoking, and perhaps most importantly, interesting book, focuses on the increasing abstract nature of both graffiti and street art. Covering topics as diverse as knit graffiti and street training, alongside more conventional sprayology and pop influenced chapters, Abstract Graffiti immerses the reader in a world of vibrant colours, political statements and folk inspired characters.

Beginning with a fantastic introduction and conversation with Patricia Ellis, the book’s main basis is a series of interviews with both established graffiti artists and new practitioners of art based avant-garde practises. Each interview covers a different topic, my personal favourites being with Barbara Kruger, Futura, and the interviews on law with the Honourable Judge Hardy, Sweet Toof and Tek33. Juxtaposed alongside some great photos, the book not only provides an extensive review of graffiti and street art, but raises questions about how you yourself view the highly controversial art forms and their impacts on public space.

For me, the only negative is that despite Cedar stating that he does not aim to outline a new form of art, at times I feel it does portray it as exactly that. However, I do say that with reservation, it’s more of a slight downside rather than any issue or problem. And this negative is completely forgotten when you start reading the final chapter – a conversation with Les Back, a professor of sociology at Goldsmiths in London. Not defined directly as a conclusion, the conversation provides a perfect ending to the book and rightly so. Les’s clear passion for graffiti and street art comes to the fore whilst you read questions and answers on society, race, and London’s over jealous planning authorities. Often these topics are not usually raised, or in fact covered, in the usual run of the mill street art book, but this book is not run of the mill, it’s a fantastically written and completely absorbing.

In short, I think everyone interested in art should pick up a copy and get reading. It’s thoroughly enjoyable and I highly recommend it.

More information can be found here on the Merrell Publishers website.

Photos courtesy of Merrell Publishers. By KR, Cedar Lewisohn, and Escif.

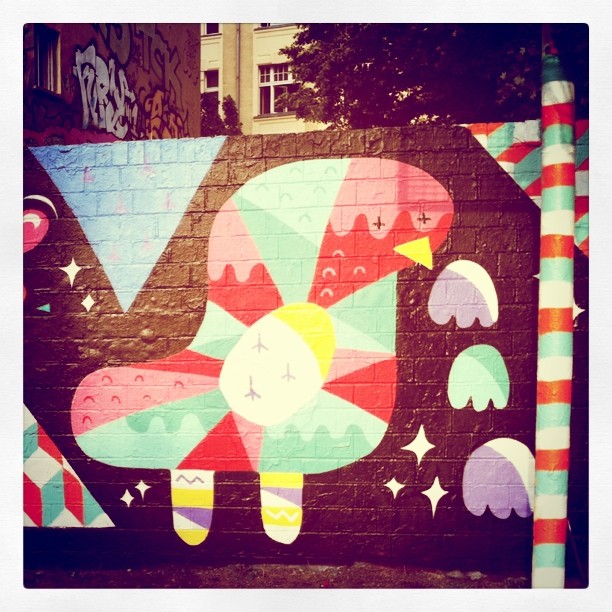

For the last 6 months, alongside partner in crime Malarky, Billy has been producing some of my favourite street art in London (and Madrid). I was lucky enough to catch up with her literally two hours before the duo’s show, Summer Breeze, opened at High Roller Society. Despite her distinct lack of sleep, Billy remained her bubbly self and her passion for giraffes, bright colours, and warm weather quickly became apparent…

“I just like painting stuff and making things look colourful. It livens up the street. And being able to paint your artwork in a large scale is great; I get a real buzz out of that. But I want to ensure that I don’t come across like a badass writer because I’m not, I just like adding colour to dull streets and making my work available to all.”

But when questioned about street art, Billy was reluctant to be labelled a ‘street artist’ due to her background, and believes the label can often be misinterpreted.

“I have an illustration background, I studied graphic design. But I have been doing a lot of artwork on the streets recently, so I suppose if that defines a street artist then I am, but I don’t come from a graffiti based background and didn’t start with traditional illegal tagging. All the work I’ve produced on the street is legal. I just like making my artwork visible to lots of people, in a space that is so accessible. But then again a lot of people prefer to do it illegally for that adrenaline rush.

Plus I think the term street art can be massively misinterpreted by some people. People say the words ‘street art’ and automatically presume you come from a graffiti background but that’s not true. You don’t need to come from that kind of background to be a street artist. Anyone can be one and do something smart on the street.

In fact, me and Malarky have done a couple of pieces for the show, doing a bit of a piss take, mainly out of ourselves but also the scene. One piece is called “Street Life” which came about when we were just listening to some hip hop and taking the piss, saying “Oh we’re so street!””

Billy, certainly raised an interesting subject with regard to the necessary qualities you need possess to be considered a ‘street artist’. Having recently read the book Abstract Graffiti by Cedar Lewisohn, I took a quote that stood out to me – “Some artists now seem to be more interested in such things as craftsmanship and drawing… It’s almost a shift from graphic art to fine art on the street” – and asked if she agreed.

“Oh yeah, I definitely think some artists are. But due to background, for me it’s just about drawing, always. That’s how I’ve developed my style; I’ve just always been really into drawing. And then just being able to take and make it big is the way I’ve come across street art.

I think there are definitely shifts and trends, and things coming out of fashion, or maybe just people jumping on bandwagons. Or they are more interested in just developing their style and technique.

And of course, there is nothing wrong with being influenced by other people and what they’re doing, when you see someone doing something really cool. Like in Madrid, 3TT Man was plastering concrete onto walls and engraving into them. And that’s just a sick idea. Obviously if you went and did that you would be biting his idea but there is nothing wrong with drawing on his, and other people’s ideas, and doing things in your own way.”

Much of Billy’s street work has been completed in collaboration with other artists; Mr Penfold, Sweet Toof, Mighty Mo, 45RPM, Richt, and of course Malarky. Having asked a bit about their working relationships and how they prepare for a colab piece, I found out it often comes down to alcohol intake…

“It’s all about our mutual love of just going out and painting, our work ties in really well together and people just get good vibes off it. Working with people like Sweet Toof and Monkey has been wicked, you learn new things, it’s got me more exposure and this show has actually come off the back of contacts through them. It’s just nice to vary it up and when you work with them it kind of opens your eyes to how other people paint.

The work we produce, kind of depends on what we’re doing and how many beers we have drunk. Sometimes we sit down and do a little sketch. I think we always have some kind of idea but it does sometimes get a bit silly and it ends up changing into someone else. When we collaborate with other people we always know what each other draws, like Mr Penfold and his characters with their weird noses, it kinds of just works. I’ve never been like “This is your part of the wall, this is mine”, its quite fluid, we mix it up a bit. And I’m learning about working with people all the time.”

As the conversation progresses, Billy explains that she has been lucky with regard to the increasing levels of buffing in London prior to the Olympics. In her words it’s been “so good, so far” and she hasn’t had any of her pieces removed. Although she admits it’s certainly going to happen one day and so taking photos and documenting her work is important.

Much of this street work has been in the form of shutters and vans, I asked about her choice of surface, which she prefers, and asked who chooses the brilliantly bright colours they use.

“I think the response we have been getting from doing shutters has been quite funny because it’s so easy; all you need to do is go into the shop and say “Can we paint your shutters?” And there are so many to paint, tonnes and tonnes in London. In certain areas every single shop has shutters. They are just easy to paint and walls and roof tops are harder to come by, it’s hard to get permission.

Malarky got into vans in Barcelona because you can’t paint shutters there anymore legally. Even if the shop lets you, there has been a law passed where the council no longer allows it. And there are tonnes of trucks there, they all park up on the side of the road and they are usually covered in tags already. It’s much harder to find a truck here that you can paint. I’ve only painted a couple but the wicked thing is about painting them is that they move around the city during the day.

The thing about shutters is they are wicked too but people don’t really see them unless its night time or Sunday. And a lot of the ones we do paint open to silly o’clock too, off licences and stuff, and so people don’t really see them. We have got lots of exposure but if they were down all the time more people could see our work.

In terms of the surface, painting a truck is just so much better. It’s so much flatter. When I first started painting a really appreciated the shutters because I could be really loose with my style. I’m really getting into doing shapes and stuff but it’s hard to get a really crisp line on a corrugated shutter. When you use a shutter it’s a bit more about doing pieces with a bit more impact with bold outlines.

Originally the colours I use come from when Malarky and I went to paint together. We used to go buy paint together and use the same colours. And then we based it on the Posca Paint Pallet. All 94 colours are quite bright and nice to work with. From there it kind of just developed where we would just get the same sort of colours each time. But I quite like mixing it up a bit – the work I’ve got in the show is toned down a bit, still bright, but not quite as in your face.”

Having popped into the gallery prior to the conversation and seen how the duo’s street work had progressed when moved inside, I was eager to ask Billy about what influences her style. And before she had to return to finish hanging her work I managed to quickly ask a bit about the show and to why it’s called Summer Breeze.

“A lot of my work is influenced from South Africa, where I used to live when I was younger, and consequently I’m really inspired by tribal and caveman paintings. I’ve got some really good African books about old artists and sand paintings that I enjoy.

But then also it’s influenced by other places I’ve visited, other art, and just all sorts of things really – song lyrics, animals, anything. To be honest this necklace I’m wearing is a massive influence. It’s got all sorts of animals in it, especially giraffes. And then there are the patterns and the animal prints, they inspire me too, and drop shadows, they are cool.

The show has sort of evolved from the time I met Malarky. When we first met it was really cold and snowing, but as we have painted more and more shutters the weather has been getting better. We even went to Madrid where it was really sunny, and here it’s just been getting progressively nicer since we met.

When you paint outside and its freezing cold that’s probably the worst situation to paint in, it’s so horrible. Your hands freeze around the can. It’s kind of just a progression into the summer. And then it also relates to the song ‘Summer Breeze’ by Seals and Crofts which I think was later covered by the Isley Brothers. It’s really just about those things and our artistic styles.”

Summer Breeze continues at High Roller Society until 3rd July, if you like Billy and Malarky’s street work then I urge you to check it out!

And if you like cakes get following Billy’s sister, Rosie. Forget Delia Smith, Jamie Oliver, and Gordon Ramsey, this girl can cook! Her little cherryade, coke and lemonade cakes went down a treat with everyone who attended the opening night. I was a sucker for the cherry ones… amazing.

Photos by Billy and HookedBlog

I normally am not this much of an ass, but this was too good to pass up and not post. I have heard about this show at Opera Gallery for awhile now, as I am sure most of you have as well. I may have been able to overlook the ridiculous name of the show, The Street Art Show, because of the incredible line-up: Keith Haring, Jean-Michael Basquiat, Banksy, Blek Le Rat, Seen, Ron English, Logan Hicks, Crash, The London Police, Nick Walker, How & Nosm, Saber, ROA, D*Face, Sweet Toof, Mr. Jago, b., Swoon, Kid Zoom, ALEXONE, Anthony Lister, Alexandrous Vasmoulakis and Rich Simmons, but then I remembered that this is still a show put on by Opera Gallery, the home of the beloved Mr. Brainwash. They do put on good show as well as some really shit ones, and I really do want this to be good, but that association still leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Plus I cannot help, but feel a bit suspicious since the show is launching on the heels of Art in the Streets.

The Street Art Show seems to be more for the collectors’ benefit who are still salivating over the interest in the LAMOCA show and want to buy more/start buying some pieces for their own collections. Well, at least Mr. Brainwash isn’t an option this time around, although i am sure he will be again soon enough.

The show opens June 17th at Opera Gallery in London.

Photo courtesy of Opera Gallery

If you looked at Vandalog this week, you’d think it was a slow week in street art. That’s not so, but I’ve been locked down working on Up Close and Personal (opening pics here). So here’s some of what I missed covering this week:

Photo by Sabeth718

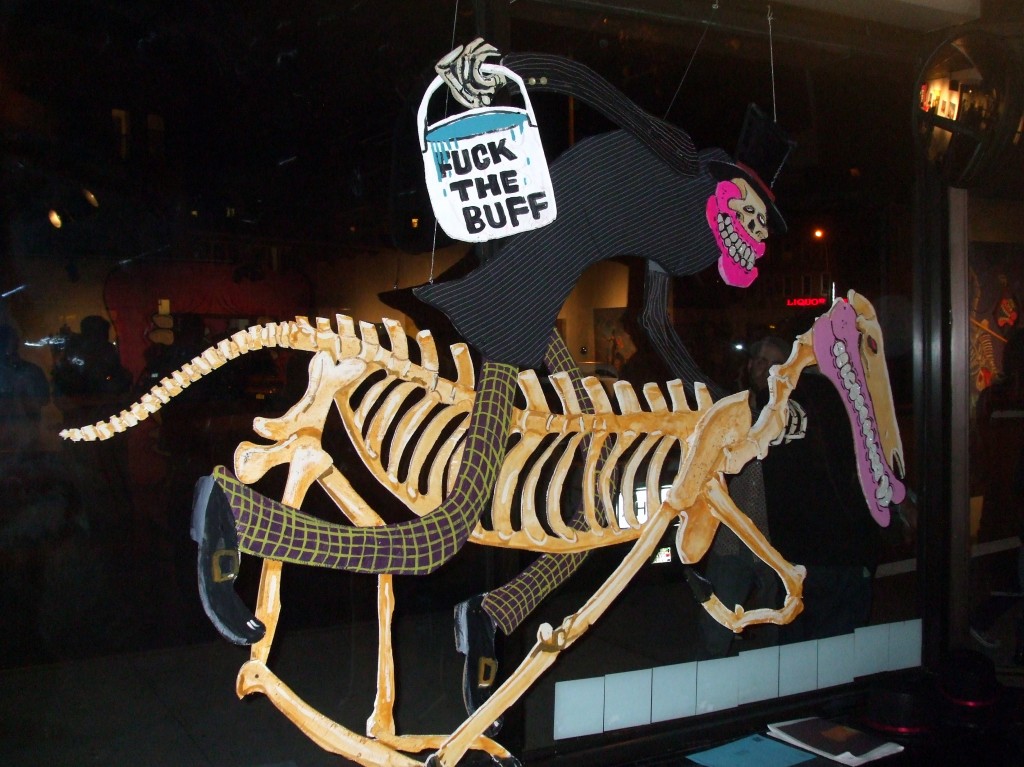

Last Friday I got to check out the opening of Sweet Toof’s new show, Dark Horse, at Factory Fresh in Bushwick. (Unfortunately, I didn’t arrive early enough to get one of the paper Sweet Toof smiles mounted on popsicle-sticks, which were given to the first visitors.) The gallery was transformed, inside and out, by large and small oil paintings, hanging woodcuts, and painted walls in the gallery’s courtyard.

Sweet Toof’s oil paintings were dramatic in a different way than his walls, like some strange version of the Old Masters, with bony horses and dogs and nobly-dressed skeletons all outfitted in his pearly whites. Some of his large rectangular canvases dominated the interior, but he also had smaller circular canvases grouped in series throughout the space. Skeletons did battle with paint rollers, in groups and one-on-one, sometimes in front of rural backgrounds, other times in some type of apocalyptic-type cityscape.

He played with using pseudo-gilded frames and sparkly paint backgrounds for smaller works, and I have to say, he may be the only artist I know of that can use glitter and horses in the same piece and still have it look amazing. More than that, though, his paintings were the type of thing you can look at for awhile and continue to see more in—aesthetically and art historically speaking, definitely, but also in the sense of morbid, symbolic hilarity.

Factory Fresh even got its own tube of Toofpaste—(artists typically use up most of the wall space in the gallery’s courtyard, but it was the first time I had ever seen anyone incorporate the vent into a piece.) All in all, a great show, and one of my favorites that I’ve seen at the gallery. Dark Horse stays up until May 22nd, and is Sweet Toof’s first solo show stateside, so be sure to check it out.

Photos by Frances Corry

Prowling the streets of East London at night, with the premise that death should be a celebration, Sweet Toof may well be the modern equivalent of Jack the Ripper, or so it may seem. But unlike Jack, Sweet Toof is not out to kill (or so he says)! Like his predecessor, this infamous character may have a penchant for top hats and disguises but rather than a knife, comes equipped with a spray can and roller pole.

As with Jack, Sweet Toof certainly leaves his mark wherever he goes – his trademark pearly white teeth and bubble gums, an ode to death but with a nod of appreciation to classical painting with a distinct Mexican undertone. For Sweet Toof, his work is not a product of a twisted mind but of a creative genius.

This month sees Sweet Toof open his first solo show in New York City at Factory Fresh. Before he flew out to the Big Apple I disturbed his last minute preparations to ask him a few questions…

I have heard you have been planning for a show in New York called ‘Dark Horse’. Can you tell me a little about what it’s about?

The show is a series of oil paintings, with sort of a street influence. And the name Dark Horse comes from the saying – “You’re a bit of a dark horse.” I like the expression, being a dark horse, it’s sort of keeping things under wraps. And sometimes if you’re being a dark horse you might end up surprising yourself and others. You just get your head down and do something a bit different, maybe it’s a bit of the unexpected.

But then also the whole horse thing is about transportation and going out on a painting mission. If you imagine going off on a mission painting, it’s like how to get away really quickly. Plus I’m into the whole Mexican Day of the Dead thing and there are a lot of horseback riders within that – the horse of death transporting the dead. But it’s generally about going on a mission, creating a stampede.

I started researching horses, looking at Muybridge’s photos and the history of horses, how they were used in battles, and the Trojan horse of Troy. Those sorts of elements allowed me to get into it as a sort of subject matter that embedded into the work.

So horses feature heavily in the pieces?

There are a lot of characters on horseback but that’s not the prime thing. It’s more about the getaway. You know, the modern day horse is the bicycle, so when you go out painting you would have your bike and your roller pole. And then it’s quite menacing, police use horses to almost intimidate people. It’s to create an atmosphere. But I’ve also used the experiences of painting outdoors, doing missions and the things that happen. And then I looked at art history and old master paintings and it sort of goes from there really.

Has New York as a city impacted upon the work at all?

It’s the skyline, the nitty-gritty nature, the lighting and the atmosphere. I’ve been once before and I’m really into the rooftops, the architecture of the buildings and those traditional water towers. I remember going across Williamsburg Bridge with a friend in his little old meter maid’s car, I looked at the whole skyline and I just found it really inspiring seeing all the lights. It’s pretty mad. Within the paintings I’ve got some little cityscapes and some water towers appear. And then there’s the whole idea of leaning over and doing reaches and stuff.

Obviously New York played a key role in the graffiti revolution but did the city and its early subway graffiti influence you too?

Massively. Subway Art and the classic documentaries; Beat Street, Wild Style, Style Wars. Most of the kids in England were really hit by that. But it was almost like once you had seen it you were cursed by it. Some of my friends managed to get away from it but I just became really addicted.

I love that whole thing of the subway trains moving through the city, just the noise of it and the atmosphere, the history of paint layers on top of paint layers, the buff, just everything. The aesthetics of it all seemed amazing. And then the mystery of all the names. We used to get up and write our names before becoming more character-based. Then I sort of came up with what I do now.

Would you note any of those early train writers in particular as highly influential for you and your friends?

I used to spend hours looking at Dondi’s whole cars in Subway Art. But also Seen, Lee, Mitch, Comet, Butch, and all the other people whose pieces you would see and be blown away by.

But really, it was just the things you got to see. Like a little cutting in a magazine, or maybe something on the telly. Back then we didn’t have the internet or any glossy magazines. It was little black and white photocopy stuff you had, or a battered up copy of Subway Art that would be tagged up and bombed.

But nowadays you can see anything at the click of a button, everything’s there. Maybe that’s helped the development of graffiti and styles, but I just loved the whole rawness when we started in the beginning, the freshness and all the break dancing and body popping, the whole energy of it all. And a lot of that energy came from New York. It wasn’t just through the art, but through all the dancing and Hip Hop music as that was obviously imported. I really fed on that energy and it came through in my painting.

Within your work, death plays a prominent role. And as you have already mentioned you are influenced by the Mexican Day of the Dead. Can you explain why death is so important to you?

When I was about 18 or 19 I experienced a lot of death in my life. I was from a small town and within a year about 10 or 11 people died in different ways. That sort of freaked me out but it was also sort of my first introduction to death.

It was friends drowning in fishing boats, car crashes, falling out of a window, burning alive in a fire, flying off a motorbike. It was a year of everyone dying who was the same age as me. It was just really freaky, especially when I looked at my school photographs and realised that half the people had gone. Death just became really familiar.

Plus I’m influenced by the Mexican Day of the Dead. They really celebrate it, and I think death should be celebrated, I wouldn’t want people to be all doom and gloom. The idea is quite fascinating as it’s all about the unknown.

That’s a pretty harrowing upbringing. No wonder you paint a lot of skeletons and teeth.

There is also the anatomy thing – that our skin is built over a framework underneath. All through art school one of the first things you look at is the structure of skeletons. I remember doing an essay on death and mortality in painting which led me onto Vanitas painting by all the Spanish masters, the symbology of the skull, and then different objects within painting, like daisies. You know, like the expression “pushing daisies.” Then little daisies started appearing in my paintings. It’s all generally about the symbology of objects, but I suppose that’s different to some of my street stuff.

On the subject of the street, you have become infamous for your teeth, hence the name. Can you explain a little about the pearly whites and bubble gums?

When you die your teeth are left. Not that I have killed anyone, but when someone finds a body that they can’t identify they will use dental records. So it’s almost like a little clue, it’s a bit fascinating.

But the whole teeth thing came from when I did letterforms. I used to put teeth within my letters, like within S’s. It’s a bit like Seen where he used eyes in his pieces. That was sort of the beginning. Plus you get those little candy sweets and I thought I would start doing those. Its just 3 colours and it came from there really.

Everywhere you go you see teeth. There won’t be a day that goes by without you seeing someone’s teeth. Maybe they won’t have any, maybe they will just have one, and some may be pretty mashed up. They are sexy, they’re aggressive, they are all sorts of things.

Do you think this content impacts on your style and your use of a range of mediums – linocuts, woodcuts, oil on canvas, screenprints and sculptural work?

I just think it’s like anything really. I love painting on the streets and I love doing a canvas. A canvas is just a portable surface, it’s light and you can carry it around with you. From painting, the obvious step is printmaking, like etching where you can get high contrasts. And when you look at different artists, you know, like Picasso, they always worked in painting, printmaking and sculptural work.

But ideas bounce between each different method. Sometimes I may do a painting and from that painting I will make a print, and from that print I may bounce back into a different painting. Or I may find myself doing some printmaking where I end up rubbing the ink away with a rag and that then may translate into an oil painting where I start rubbing around the paint. It’s like a visual language. When you do these different processes and different approaches to making stuff you create this language of image making and composition. So its feeds into each other, it all interlinks.

We have talked about your work indoors, but how do you approach painting on the street?

I quite like going out and not knowing things and just being spontaneous, and a lot of my work is done on the spot. Although I’ve done some walls recently with a friend, we planned things out a bit more and that’s nice. You sort of just look at the wall and see the maximum you can get out of it.

When I plan a wall, sometimes I will take photos and go away with an idea. But that idea may change to something else, so it’s always a little unpredictable. And even after it’s done you may think “Fuck I could have done this or done that in a different way.”

I heard that you left Burning Candy last year, but you mentioned that recently you have been working a bit with a friend. Do you prefer to work alone or in collaboration with someone else?

Yeah, I decided to leave last year, it just seemed right. And recently I have been working with [Paul] Insect, doing a few reaches. I like both – working on my own and going out with a friend. I used to love going out on my own and sometimes it’s safer I think, as you’re not looking out for someone else. But then again, sometimes it’s more risky as there is no one looking out for you. It depends, but obviously you just need someone that’s close and you can depend on and work well with. I like a bit of both really.

It’s been really great working in collaboration with people, but I think it’s equally as important to stand on your own two feet. I’ve been on loads of missions on my own and sometimes you just think “What are you doing?”, but I seem to feel more alert, I hear more, but may be a little bit more paranoid. And then funny things tend to happen to me when I’m on my own, like the time I thought someone threw a brick at me while I was doing a piece alongside a canal at night… it turned out to just be a big fish!

When you are out painting on the street you seem to use both a spray can and a roller pole, but which is your favourite?

I think maybe the roller pole, just because of the height you can get with it. And also, with a bucket of paint you have so much more coverage. It’s drawing on a large scale and it’s like trying to draw something with a mop. The control element is slightly different. With a spray can you can actually cut back and work into it, but with a roller pole I like the speed, and while it’s messier I think that’s probably why I like it. It feels more powerful in a way. Then again, with a spray can you can get fades and things you can’t get with a roller pole.

Do you ever feel the urge to go back to your roots and just go tagging for a night?

All the time. Although I do what I do, you see other stuff and you think “Oh I’d like to do that.” But I think you always return to your roots and you never forget your roots. I think that goes for style too and even the way styles progress, through the influence of New York and then the electro scene, old letterforms or maybe the stuff you saw on TV.

How do you feel your street work impacts on the city and public space? Is it about reclaiming space from the advertisers?

I’m not sure it’s really reclaiming space as I think that space can be anyone’s. You are forced to look at all sorts of advertising and that’s accepted. And if you have lots of money can put up whatever you want. Although if you go out there and do it off your own back, put stuff up, then it’s seen as vandalism, but that’s an argument people have had for years.

For me it’s more about making a head turn when people walk along. Making them ask, “Who’s done that and why have they done it?” Sometimes you don’t even know yourself and you go into a sort of trance but its nice to make people have a little chuckle, and some may start asking, “How have they done that, what were they thinking or what are they doing now?”

I suppose when I started I was a little more mindless and just put things anywhere, but then you get to the stage when you actually start looking at something. You think about the architecture, the space and the different parts of the space. I worked with Insect recently on a piece and brought animation into it. We started to think about how to use the space and how to max out the space, to do different things with the space.

That’s refreshing to hear as often an artist will never consider the space where their work is displayed. But, what is the piece you are most proud of?

I’m not particularly proud of any piece. I tend to look at them all and cringe and think “What am I doing?” I suppose I like things you can’t believe you got away with. You cannot be too precious with it because its outdoors and people may go over it, you need to let go. I think that also keeps the drive going though. If it was the perfect piece, something “Wow”, I think my vibe would be gone and I would just think that I have done it all.

So you’re always striving to better yourself?

There is always that hope that the next piece will be better than the piece you have just done. You have to keep the drive going. There are times when you think “What was I doing?” but that just adds to the drive to improve and the need to keep putting pieces on the street.

What do you think the future is for Sweet Toof?

To me painting is almost like a medicine – you have to keep it going outdoors in order to be able to work indoors. And as such I think what I have experienced from painting outdoors creeps into my paintings. I suppose I feel that I wouldn’t be able to make that work without going through the process of working on the street. Maybe there will be a time when I can retire, and just end up painting some watercolours and that will be it. But I think I will always end up doing cheeky little pieces outdoors.

So we can hope to see you collecting your pension holding a spray can when your 70 years old?

Ha ha yeah, going out tagging. It’s mad though, I’ve said it once before to someone that you become like a “Graffaholic”, you try and give up, and you try and do things the right way but there’s always that temptation. But there are times when the risks aren’t worth it when you have all this stuff going for you and you could lose it all. I suppose that does keep you on your toes.

Anyway, the future… perhaps I could just be really cheesy and say “I hope to take a big bite out of the Big Apple!” Ha ha, that’s the future!

Dark Horse opens at Factory Fresh on Friday, April 29th at 7pm and runs until May 22nd.

Photos by Sweet Toof and Paul Insect.