These last few weeks, I’ve been processing Banksy‘s Better Out Than In residency project and reading what other people have had to say it about it. Now, some mainstream media outlet like Forbes writes a silly article about Banksy and focuses almost entirely on money using numbers pulled from thin air, I understand. And hey, Jerry Saltz isn’t a fan or someone with a background in street art or graffiti, so of course his list ranking the pieces in Better Out From In from terrible to less terrible is a somewhat ridiculous. What really upsets me is when writers on media outlets that should know better miss the point entirely. Two articles in particular, in Juxtapoz’ print edition and on Complex’s website, struck me as particularly off-base.

The latest issue of Juxtapoz arrived in my email inbox on November 12th, so it’s very possible that Nick Lattner wrote at least the majority of his article before Banksy finished Better Out Than In, which is just the unfortunate reality of print journalism from time to time I suppose. If that was the case, I understand why Lattner went for writing about Banksy’s use of social media during Better Out Than In than the works in the show. Or maybe it was an attempt to stand out among the hundreds of blogs and magazines doing round ups of the top X pieces in the show. Whatever his reasoning, Lattner tries to argue that the real brilliance of Better Out Than In is how Banksy showed “a mastery of [his] command” of social media and the internet for getting his work out there. Lattner praises Banksy’s use of an Instagram account, a website and a hotline for audio-descriptions-by-phone.

None of that was innovative. It might have been cool, but it was not new. Cost and Revs listed a working phone number on their wheatpastes in the 1990’s. Banksy has had a website for years, as have most serious street artists, and Banksy was late to the game joining Instagram. Was it a surprise to see Banksy on “social media” networks? Sure. But only because he’s anti-social. And once on Instagram, he used it to push out content, not to engage. What Banksy did by putting his work on his website and posting it to Instagram was not innovative. It was simply not being stupid, assuming he wanted as many people as possible to see his work. Why is Lattner applauding a lack of stupidity like it’s a stroke of genius?

Similarly, Leigh Silver over at Complex.com wrote an article with the headline Banksy’s “Better Out Than In” Took Place on the Internet, Not the Streets. I’m very pleased to see Silver writing something of such substance on Complex and she connects the show to a larger narrative about street art and graffiti online that I think is important to understand, but I disagree with her somewhat. Basically, she argues the same thing as Lattner with regard to Banksy: That the noteworthy aspect of Better Out Than In was that Banksy was posting this photos online. That’s where most people saw the Better Out Than In, and it helped to “preserve” the show in a sense by allowing it to be seen in photos even after the work was tagged over or otherwise destroyed. That’s all true, but I wouldn’t say that’s what was noteworthy about Better Out Than In.

On the one hand, with a book on basically the topic of street art and the internet coming out soon, I’m excited that other people have picked up on this shift. That said…

- Even Silver admits that this has been the modus operandi of other street artists for years. It isn’t like Banksy just suddenly invented the idea of people seeing street art online.

- Banksy himself has done work that’s made to be seen on the internet before (for example).

- Seeing the work online was an option, but it’s not what Better Out Than In was about. Banksy is more interesting than that.

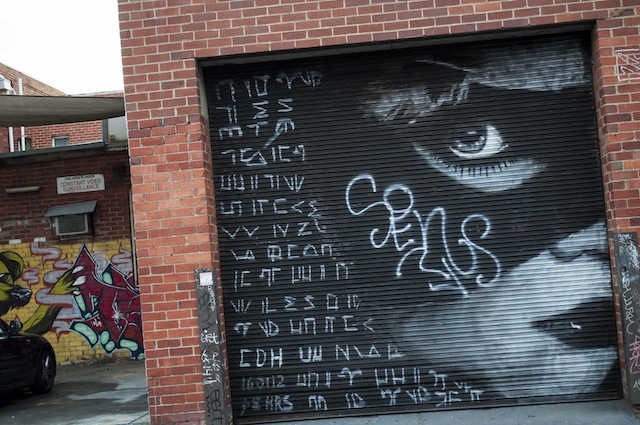

We need more people like Silver, people who suggest that “maybe ‘getting up’ is not on the streets anymore; it’s on social media,” but it seems odd to cite Better Out Than In as a prime example of that mindset. While there were a handful of pieces in the show that were meant to be seen online or really only existed online, there were many more pieces that were intended to be seen in person. Many of the best pieces in Better Out Than In begged for, or even required, crowd interaction to be activated and seen as complete. Here are the ones I’m thinking of:

- This is my New York accent – Perfect placement for people to crouch down and take photos while flashing fake gang signs.

- You complete me – Dogs peed on it.

- Truck delivering “calm” – This truck was supposed to be delivering calm, but really it delivered endless chaos as fans chased it down the street and crowded around for a photo.

- Balloon heart – You mean to tell me photos like this one weren’t the point of this piece? Oddly, this is a piece that Lattner cites as one of his favorites.

- Banksy beaver – Maybe crowds weren’t intended as essential to this piece, but Lattner cites this video as evidence that the show had a focus on digital experiences, which is ridiculous since the video only exists due to the actions of people at the site of the piece.

- Sirens of the lambs – Yes, the video of this piece is great, but it’s one of those pieces where the experience is 10x better in person.

- Confessional – Again, this is about the crowd staging photographs. Yes, those photos are shared online, but a crowd needs to be there away from keyboard as the first step.

- Central Park stencil sale – Even this piece, which it seems no hardcore Banksy fans saw in person, required some crowd interaction or lack thereof. Without that, what’s the story?

- Twin Towers tribute – Many people have suggested this was Banksy essentially daring people to tag over the work. Who would dare tag over a 9/11 tribute piece?

- Big mallet – More site-specific posing.

- Sphinx – Just like many ancient Egyptian ruins, Banksy’s work is often subject to looting.

- The banality of the banality of evil – How much will you pay for a painting of a Nazi (okay, admittedly this auction took place online…)?

Better Out Than In was not about the internet. It was not about Banksy “broadcasting” his work to an Instagram audience as Lattner suggests in Juxtapoz and it did not primarily take place on the internet as Silver suggests, at least not any more so than 99% of mainstream street art today. Yes, Banksy utilized the internet, but for the most part only to the extent that any reasonable street artist utilizes the internet. In fact, Banksy probably had more of a focus during this show than most contemporary mainstream street artists have in their work on away from keyboard crowd interaction and response. What Silver and Lattner are noticing is street art in general, not Banksy.

If you want examples of street art that exists on the internet and was actually designed to exist there, check out the other examples in Silver’s article, or these posts I’ve written, or wait for my ebook Viral Art, which will be out in a few weeks.

Photo by Ray Mock