Via Unurth

Can Banksy die? I’ve got no doubt that the man who was writing the name Banksy on Bristol’s walls in the 1990’s can and will, at some point, die. That’s not what I’m wondering though. Keith Haring has been dead for more than 20 years, but you can still buy new products with his imagery. Similarly, Basquiat’s estate released prints after his death. But those artists had names and faces. Even after their deaths, products can still be made using their images, but there’s not going to be any new imagery. But Banksy (the brand, not the man) doesn’t have those same constraints. Disney didn’t die with Walt Disney. Is Banksy one man or many people?

While he is anonymous, Banksy is publicly portrayed as being one person. But what does that one person actually do these days when it comes to making art?

Does Banksy paint his own street art? Shepard Fairey has said that he doesn’t (thanks to Mischa for the link to that article) and, in the latest issue of Very Nearly Almost, Eine says that he used to paint street pieces for Banksy. Given his high-profile status and the risks associated with painting outdoors, it probably makes legal sense for assistants to paint Banksy’s street pieces. If I were in Banksy’s position, I wouldn’t risk painting all of my own outdoor work. Even if Banksy does paint his own street pieces today and has always done so up until today, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to notice if that situation changed tomorrow.

What about his indoor work? Maybe Banksy still paints everything himself, but I’m doubtful of that. While hiring assistants might be more difficult for Banksy than Jeff Koons, it’s clear in Exit Through The Gift Shop that Banksy has a staff. At the very least, I think it’s safe to assume that Banksy isn’t executing the creation of any his sculptures himself (no matter what this video purports to show). And there’s little reason to think Banksy doesn’t have assistants completing part or all of his paintings. Banksy has said that he paints his own pictures, but how would anyone outside of his team know if he was telling the truth or not? Assistants who work on paintings for an artist are a widely accepted practice. As an extreme example, Damien Hirst has said that his best spot paintings were the ones painted entirely by Rachel Howard, his former assistant. Even if Banksy paints all his own pictures today, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to know if that practice changes in the future. Again though, some use of assistants for painting is probably what almost any artist in Banksy’s position would do.

But regardless who who physically executes the artwork, conceptual artists have long contended that the artist is the one who comes up with the idea of the art, not the one who makes the art. By that standard, what makes a Banksy a Banksy is that he came up with the idea, but he isn’t the only one who could do that. Countless artists emulating Banksy, as well as generations of political cartoonists, have shown that coming up with clever 1-liners isn’t a skill possessed only by one man. Admittedly, I think most people find Banksy’s average success rate with his jokes to be higher than that of a lot the people he has inspired, but that is probably as much about being careful with what you put out there as it is about being clever. Maybe it’s true that no one person will ever be as good as Banksy at his brand of humor and commentary, but a dozen people working together probably could be. But I’ve already made an assumption here: Today, there is only one individual who comes up with all the ideas behind Banksy’s artwork. Again, we have no way of knowing how true that assumption is. Banksy’s cloak of anonymity means that the public really has no idea how many people contribute ideas to the Banksy identity. Today and in the future, the ideas behind Banksy’s art could come from one man or a team of 50 with no input from the original individual who called himself Banksy. How could we tell the difference?

I’m inclined to think that Banksy, the man, is a hard working guy who does involve himself in the making of the artwork that he signs. But given all the possibilities for others to be involved in the Banksy brand without the public knowing a thing, it is clear that the Banksy brand can continue to create artwork indefinitely with or without the original man behind the name. Like the many boys who took on the role Batman’s sidekick Robin (oh, haha okay I came up with this metaphor days ago and only now as I write it down do I realize the irony given Banksy’s supposed identity. I’m an idiot), an anonymous artist’s name and image can be taken up by any number of people. If the man behind Banksy ever leaves the Banksy organization, or when he dies, will the public ever know? It’s possible that my grandchildren will be able to see “original” Banksy artwork completed a century from now. Banksy seems to have reached the absurd hyperbole of conceptual art: the original artist may not even need to conceive the artwork for it to bear his name. Banksy has finally achieved what Warhol and others set out to: the artist is truly a brand without a human identity.

This isn’t to say that Banksy’s death is impossible. It may happen one day. It seems only right that Banksy the brand dies with Banksy the man and it may very well end there, but it would definitely be possible for his team to continue the brand without the man. Then, the questions become would we notice, would we care and how would Banksy the brand change itself from the original intent of Banksy the man?

What do you think? Does Banksy’s death promise a new frontier for art? Have I completely misunderstood the brand/man that is Banksy? This is a post of questions I’ve been thinking about more than it is a post of answers and opinions, so I’m looking forward to reading other people’s thoughts in the comments.

Photos by eddiedangerous, Jake Dobkin, caruba, Joshua Rappeneker and ahisgett

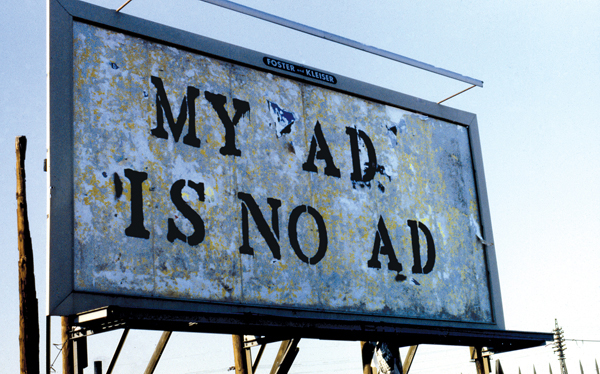

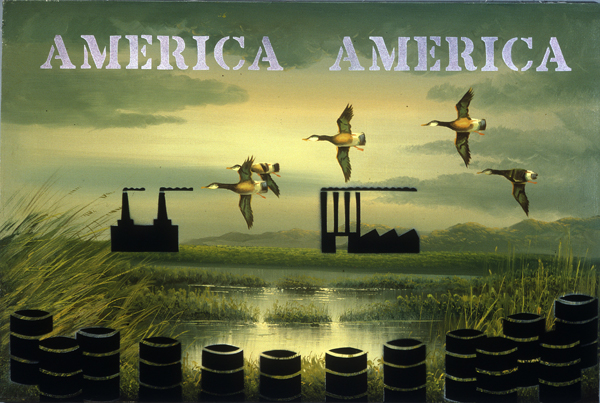

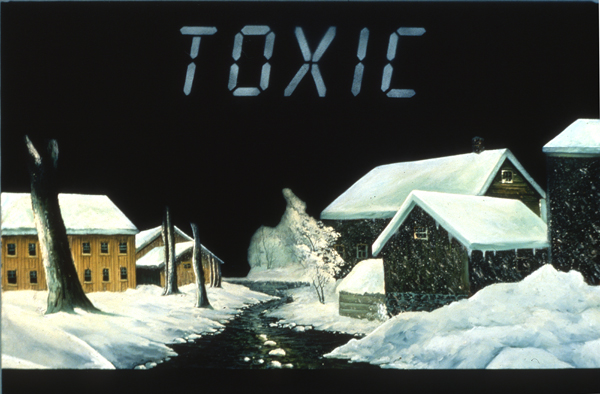

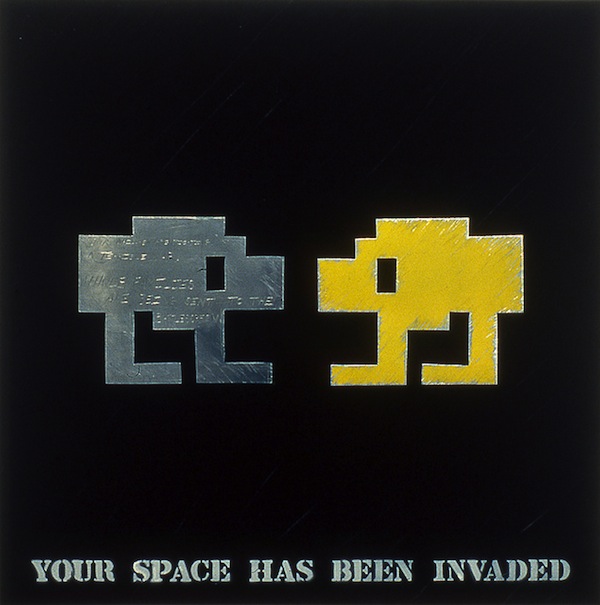

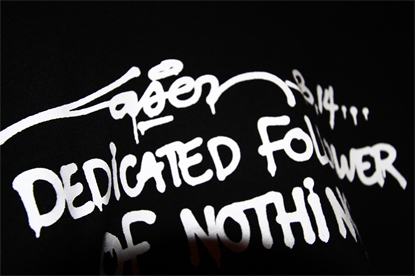

One of my favorite artists, and maybe the most under-appreciated artist from the first wave of street art, is John Fekner. These 10 artworks are some of favorites from Fekner and his collaborator Don Leicht. They were made between 1980 and 1993.

Fekner is probably best-known for the the text he stencils outdoors in New York City:

Leicht and Fekner always seem to be making art far ahead of their time. Here are a few examples:

And finally, Fekner has also made video art and music. Here a video from 1981 called Toxic Wastes From A To Z:

Photos courtesy of John Fekner

Other aka Troy Lovegates is in Buenos Aires and I’m loving these new street pieces from him. Sometimes it can be better to go small with great placement and resist the temptation to paint something huge at the first big wall available.

Photos by Troy Lovegates

After today, I’m going to try to avoid posting or commenting about this whole Blu/Deitch/MOCA series of blunders until at least April because I think I’ve pretty much said I feel needs to be said. After having a number of discussions with some people I respect, some who agree and some who disagree with what I’ve said in the past about all this and who’s insights helped me to better strengthen and develop my own opinions, and with some new statements and facts coming out, it seemed worth writing a bit more about all this. Anyway, the actual post with my thoughts on all of this…

I think that those of us on different sides of this debate disagree less than some people realize. Mostly, we seem to see the responsibilities and rights of a museum differently.

What I’ve seen from all this are the difficulties of bringing street art into a museum context. It is important that art history and museums recognize the street art and graffiti movements, but it isn’t easy to do. A show of only work on canvas or screenprints or other “gallery art” clearly wouldn’t be a street art show, but the Tate Modern missed an opportunity by keeping things outdoors. So it seems that the solution would be a show that mixes outdoor projects with a gallery component, like MOCA is planning to do in April. Except that a museum cannot commission street art. They can commission public art by street artists, and there is a difference. Public art, such as that commissioned by MOCA, comes with certain responsibilities and considerations that do not exist in street art.

That’s why festivals like FAME, Primary Flight and Nuart are so important. Their focus is on bringing street art and graffiti to an area, and they don’t have the same considerations of museums. A lot of what goes up at FAME still goes up illegally and without anyone’s permission. While museum exhibitions are important for securing street art the place that many people believe it deserves in art history, those mural projects are of at least equal importance for actually bring new street art into the public space.

Blu says he was censored. I respect Blu for not bowing to the concerns of working in a museum context and not subjecting himself to “self-censorship,” but public art involves what Blu would term self-censorship. Until Blu’s statement, I had been under the impression, now obviously incorrect, that Blu might be returning to paint another mural for MOCA. That made me feel less upset about his wall getting buffed. Unfortunately, Blu will not be returning. It’s too bad, because as I’ve said before, a mural by him could have been a highlight of MOCA’s street art exhibition, but I respect Blu for sticking to his principles.

That doesn’t mean that Deitch was wrong to remove the mural though. It was a difficult decision well but within his rights as a curator and museum director. It is not the decision that I wish he had made and I highly doubt that Deitch took any joy in his decision either, but it may have been the right move for the exhibition and more importantly I can see why it would be the right move for the museum as a whole.

The (admittedly imperfect) analogy that I’ve come up with for this situation goes something like this: A curator at MoMA is putting on a show and wants to include a new painting by Murakami. Somehow through some crazy miscommunication with Murakami’s studio, a painting arrives that the curator hates or for whatever reason cannot be included in the exhibition. The curator screwed up. He should have communicated his thoughts more clearly to get something closer to what he wanted to include in the show. What does the curator do? He sends the painting back to Murakami and doesn’t include it in the show. That’s part of his job as curator.

Unfortunately at MOCA, that situation played out in public and in the artwork had to be destroyed instead of being sent back. MOCA removed a mural that they had not approved to have painted (they asked Blu to paint a mural, but mistakenly did not approve a specific design beforehand) in the first place. In that sense, I can certainly appreciate the argument that MOCA buffed a piece of street art, and that’s ironic and not desirable.

Probably the person who has expressed his balance of support for Deitch with disappointment in the destruction of the mural best is Shepard Fairey (and I’ve used some of his ideas in this post). Here’s some of what he said to The LA Times:

However, a museum is a different context with different concerns. It would be tragic for the break through of a street art /graffiti show at a respected institution like MOCA to be sabotaged by public outcry over perceived antagonism or insensitivity in Blu’s mural. Graffiti is enough of a contentious issue already. The situation is unfortunate but I understand MOCA’s decision. Sometimes I think it is better to take the high road and forfeit a battle but keep pushing to win the war. Street art or graffiti purists are welcome to pursue their art on the streets as they always have without censorship. I think that though MOCA wants to honor the cultural impact of the graffiti/street art movement, it only exists in its purist form in the streets from which it arose.

No matter how hard they try or how much some people wish this were not true, institutions are not the streets. Once upon a time, Banksy put this very well on the side of the National Theatre in London:

I’m about to get my virtual ass kicked with this post. This might get more negative comments than anything I’ve ever written before. I know that. Any yet, here I am.

On Thursday, word hit the internet that Blu had painted a mural on The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA in LA but that it had been whitewashed. On Saturday, Vandalog was the first site to publish any official comments from MOCA. And late on Monday, The LA Times has finally published some substantive comments from museum director Jeffrey Deitch about the whole series of events.

Here’s a selection from the article:

Reached by phone while traveling, MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch confirmed that he made the decision because the mural was “insensitive” to the community.

“This is 100% about my effort to be a good, responsible, respectful neighbor in this historic community,” Deitch said. “Out of respect for someone who is suffering from lung cancer, you don’t sit in front of them and start chain smoking.

“Look at my gallery website — I have supported protest art more than just about any other mainstream gallery in the country,” he added. “But as a steward of a public institution, I have to balance a different set of priorities — standing up for artists and also considering the sensitivities of the community.”

He rejects the talk of censorship. “This doesn’t compare to David Wojnarowicz. This shouldn’t be blown up into something larger than it is,” he says, describing a curator’s prerogative to pick and choose what goes into a show. “Every aspect of the show involves a very considered discussion.”

The unfortunate thing, he acknowledges, was the timing, as the artist began the mural while Deitch was out of town earlier this month for the art fair in Miami. “Blu was supposed to fly out the second-to-last week in November, so we could have conversations about it in advance,” Deitch said. “But he said he had to change his flights, so he ended up working in isolation without any input.”

When he returned from Miami and saw the mural, then more than halfway completed, Deitch said he made the decision to remove it very quickly, unprompted by complaints. “There were zero complaints, because I took care of it right away.” He asked Blu to finish the work so it could be documented as part of the exhibition and appear in the accompanying catalog.

I’ve got to stand by Deitch 100% on this. Besides the very legitimate reasons he mentions for removing the mural, his appointment to MOCA was a very controversial one. We don’t live in a perfect world, and this was a pragmatic move which takes into consideration the larger concerns of MOCA and the LA community. Yes, this whole thing was a poorly managed series of unfortunate events resulting in a great artist’s work being destroyed (after, what I assume was extensive documentation which is how the vast majority of street art and probably art in general is viewed these days), but Deitch made the right move for the wider museum. Things shouldn’t have gotten out of hand, and they did, but Deitch has acknowledged that. Look at the situation from Deitch’s perspective when he showed up in LA to a half-finished mural that he knew would not work.

Deitch made a curatorial, respectful (of the LA community) and politically pragmatic decision to remove a work from an exhibition that he had not approved for inclusion in the show. If he had seen a sketch beforehand (as he should have), let the wall get painted and then removed it, this would be a very different discussion. Although some have suggested that this signals disaster ahead for his upcoming street art exhibition in April, I am not so sure. Sebastian at Unurth and I have a friendly bet going based on the average of reviews of MOCA’s street art show in the LA Times, Unurth and Vandalog: If the reviews are positive, he buys drinks next time we see each other and if the reviews are negative, I have to buy the drinks. So we’ll see how that turns out in a couple of months.

Photo by vmiramontes

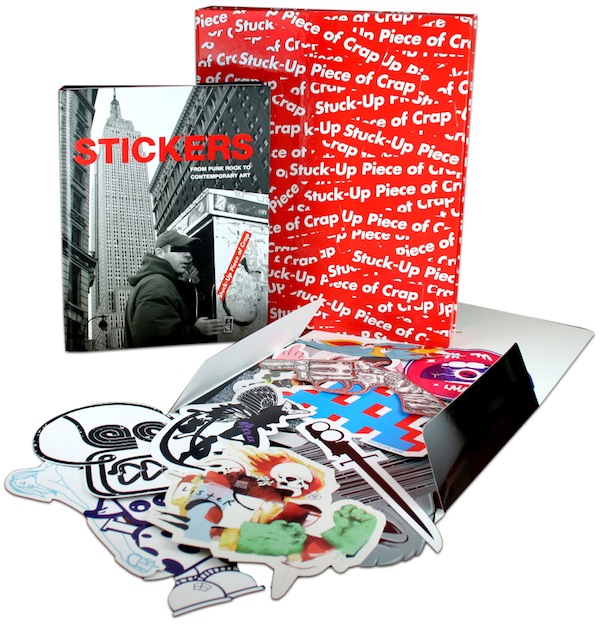

After procrastinating and procrastinating about writing this post, I missed Hanukkah and Eid, so I guess this is a gift guide for Christmas. Sorry for the delay.

Here are a few street art related products that have come out in the last year or so that I think are pretty cool. If you’re looking for a last-minute holiday gift for the street art obsessive in your life, hopefully this will help…

Or, if you’re a street artist, you could go out on Christmas, brave the cold, and do some art. Give a gift to the rest of us. Not enough street art happens in the winter months.

Here’s a hodge-podge of photos of some of my favorite murals from Miami this year… Probably more to come in future posts as well. Most of these were part of Primary Flight.

Photos by S.Vegas, Hargo, tatscruinc and courtesy of Thinkspace and Remi

The street art community has been in a bit of a hubbub over a mural by Blu being painted over less than 24 hours after it was completed. Until now, MOCA, the museum that commissioned Blu to paint the mural on one of their walls, had stayed silent on why the mural was removed. In my post I tried not to jump to conclusions, but given what’s going on at the Smithsonian and the silence from MOCA, it was hard not to speculate and assume the worst: pointless censorship. Some people also speculated that the whole thing was a preplanned stunt. Luckily, it sounds like all this was just a series of unfortunate events, but with a reasonable explanation.

I’ve just received word from MOCA as to what happened:

MOCA commissioned Blu, one of the world’s most outstanding street artists to create a work for the north wall of The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA.

The Geffen Contemporary building is located on a special, historic site. Directly in front the north wall is the Go For Broke monument, which commemorates the heroic roles of Japanese American soldiers, who served in Europe and the Pacific during World War II, and opposite the wall is the LA Veterans’ Affairs Hospital. The museum’s director explained to Blu that in this context, where MOCA is a guest among this historic Japanese American community, the work was inappropriate. MOCA has invited Blu to return to Los Angeles to paint another mural.

Certainly not the way you want mural projects to go, but if Blu understands and respects MOCA’s decision enough to paint another mural there, then I do too. This was not the pointless censorship that it has been painted to be by the internet, it is being respectful to the community that would be living with this art every day.

Photo by Unurth

I heard the most wonderful news recently: Blu was about to paint a huge mural in LA. This week, that’s exactly what he did. Blu was invited to paint the wall by MOCA, the museum where Jeffrey Deitch is about to put on a major street art exhibition. In fact, the mural was painted on one of the walls of MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary. A mural by Blu would probably be, for me, a highlight of that exhibition. Unfortunately, less than a day after the mural was finished (and yes, it had been finished), it has been completely painted over by MOCA workers. What’s going on here? So far, nobody really knows. MOCA has declined to comment.

Unurth has more images, GOOD offers some speculation and LA Downtown News has a bit to add to the story. Most interesting given the content of Blu’s mural, LA Downtown News notes that the mural faced a Veterans Administration building and was also within sight of a war memorial. No evidence to say whether either of those things factored in to why the mural was removed though.

The buffing of this mural is especially worrying to me given the current controversy at the National Portrait Gallery about the removal of controversial art. Hopefully there will be more answers about what is going on in here in the next few days.

Photo by Unurth