Well, really, the headline here isn’t entirely accurate. The artist and collector Martin Wong saved the seeds of a culture, and then donated his collection the Museum of the City of New York. And then the museum mostly kept those seeds hidden away for about twenty years. But now the museum, with the help of curator Sean Corcoran and others, has brought those seeds back into the spotlight for a new generation to learn from. Of course, I’m talking about City as Canvas, the new show at the Museum of the City of New York, and the seeds I’m talking about are the seeds of modern graffiti.

The back story behind City as Canvas is pretty great. Wong, a painter who lived in NYC’s East Village in the 80’s, was noticing graffiti and as he met some of the men and women behind it, he began supporting the young writers by buying their work. Eventually, that turned into a major collection of work by New York train writers like Sharp, Daze, Lee, Futura and many more. Wong even tried to open his own “Museum of American Graffiti” in 1989, but it didn’t work out. Still, Wong had amassed something special and unique that captured a very important time period for graffiti as artists transitioned from trains to canvases and teenagers to adults, and as graffiti itself spread from New York City to the rest of the world. Eventually, he donated his collection to the Museum of the City of New York. Those are the basics, but really, the story of Wong’s collection has already been told very well and in more detail in the New York Times, so do check out that article.

As for the show itself…

Some of the work in City as Canvas is stunning. There’s Lee Quiñones’ bold and vibrant Howard the Duck painting, which left my awestruck in person even though I thought I already knew what it looked like. Historically, it’s an important piece because it’s a recreation with brush paints of a key mural that Lee painted in 1978, but it also just looks great and packs as much punch today as it did when it was painted in 1988. It’s an artwork made for a gallery but emulating graffiti, and it still works. That’s rare. And keep in mind that I say this as someone who also generally doesn’t care for straight up pop art paintings or pop art plus graffiti letting. Even with that bias, I love Howard the Duck.

The section of work that focuses on the early abstract writers like Futura and Rammellzee is fascinating and impressive, particularly given how hard sites like Graffuturism have to push even today for abstract graffiti to get the recognition it deserves. Although to be honest I had never paid much attention to his artwork before, the late A-One‘s largely abstract work blew me away. Sharp’s wildstyle verging on abstract wood cutout work shows how far writers were pushing things even in the 80’s. It wasn’t all just simple throw ups on big rectangular canvases.

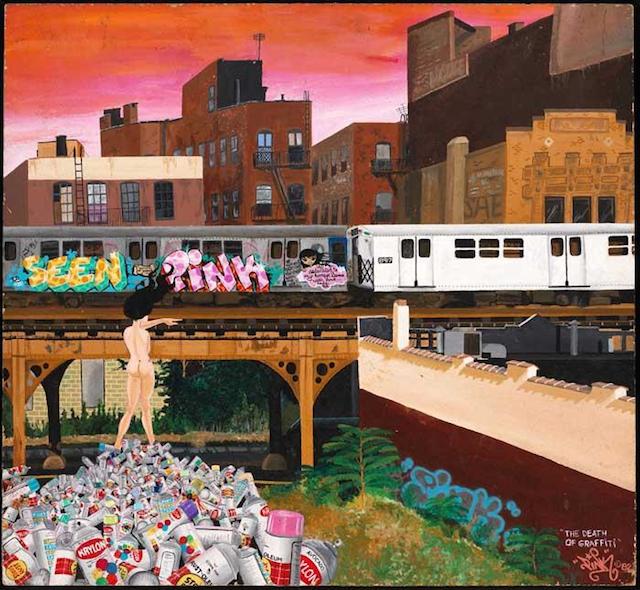

Lady Pink, who I have a deep respect for and whose work I like just fine but I don’t generally seek out with a passion, has one of the best paintings in the show with 1982’s The Death of Graffiti. The painting is beautifully done and the message tugs at my heartstrings.

Much of Wong’s collection is made up of black books and black book sketches. Some of them are artistic gems. From the sketches, I gained a new appreciation for Zephyr and Lee in particular.

But not everything in City as Canvas is gold, at least not if you take it out of context. The works I’ve mentioned so far are brilliant and timeless, and there are others like them in City as Canvas, but a lot of the sketches, paintings and sculptures are more important for capturing a critical moment in graffiti history than their aesthetic or conceptual value outside of that timeline.

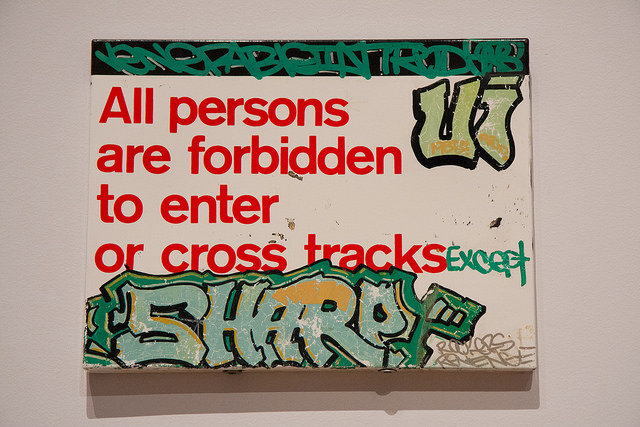

The above piece by Sharp isn’t something that I would want on my wall for his unmatched lettering ability or for any other reason, except that it is important as a piece of an era that ended up shaping the world. Much of City as Canvas is like that. I imagine I’m going to get some hate from writers right about now, but I’m not saying the work is bad. I’m just saying that Sharp was about 17 when he painted that piece, which means he may have been pushing art forward at just 17 and that’s amazing, but today that work doesn’t interest me aesthetically in the same way it might have interested writers or just art fans back in the early 1980’s. Similarly, Wicked Gary’s collection of tags from the early 70’s literally includes one tag that just says “GAY” in handwriting worse than my own, but there’s history and innovation in that tag collection too.

In the context of graffiti’s history and art history in general, even the works in City as Canvas that wouldn’t catch my eye if I saw them on a gallery wall today interest me for their historical value. Contemporary graffiti was originally developed by a bunch of amazing kids and young adults. They were innovating, inspiring each other and producing artwork that got themselves and many others genuinely excited. Not all of those works catch my eye today, but they have a place in history and they are absolutely special for that. You just have to take the time to understand them in context, something City as Canvas provides.

Because of these works that the uninitiated might not immediately identify as brilliant, even though many are just as important if not moreso than the pieces I started this review with, City as Canvas is a much more difficult show than you might imagine when someone says, “There’s a graffiti show at the museum.” Once you get beyond the showpieces, the colorful masterpieces that serve as a great way to get people in the door, and start looking closely at the works whose value relies more on historical context, you begin to understand the early evolution of graffiti on a level that an exhibition focusing only on the superstars of graffiti could not possibly accomplish. Frankly, there are things in City as Canvas that might at first read as absolute crap, and that’s a good thing.

Isaac Newton wrote, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” I’m 23, and I know a lot more about street art than I know about graffiti. I was born after most or perhaps all of the art in City as Canvas was made. All the graffiti I’ve ever seen in person and most of the graffiti that today’s mainstream public is willing to call art, has been produced by writers standing on the shoulders of giants who were standing on the shoulders of even more giants who came before them. City as Canvas is an opportunity to understand and remember that. It includes the giants, but also the giants before the giants and the giants before that, and so it is an invaluable exhibition to those of us who came late to graffiti, as all future generations will. Those under-appreciated early giants need to be recognized and understood, and City as Canvas is a big step in the right direction.

Do not miss City as Canvas, open now through August 24th at the Museum of the City of New York. There, you’ll find the seeds and a few young saplings of the dense and mighty forest that is graffiti today.

Photos courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York and by gsz