Why do people collect art? Perhaps part of the reason is a memory or an experience associated with the object. The possessions I have most affection for were bought on holiday or given to me by a friend. There’s a cool story that goes with them. If we accept that artistic experience is in part about feeling a meaningful connection with an object, can the process of collection also elicit emotions and memories, beyond the aesthetic of the work?

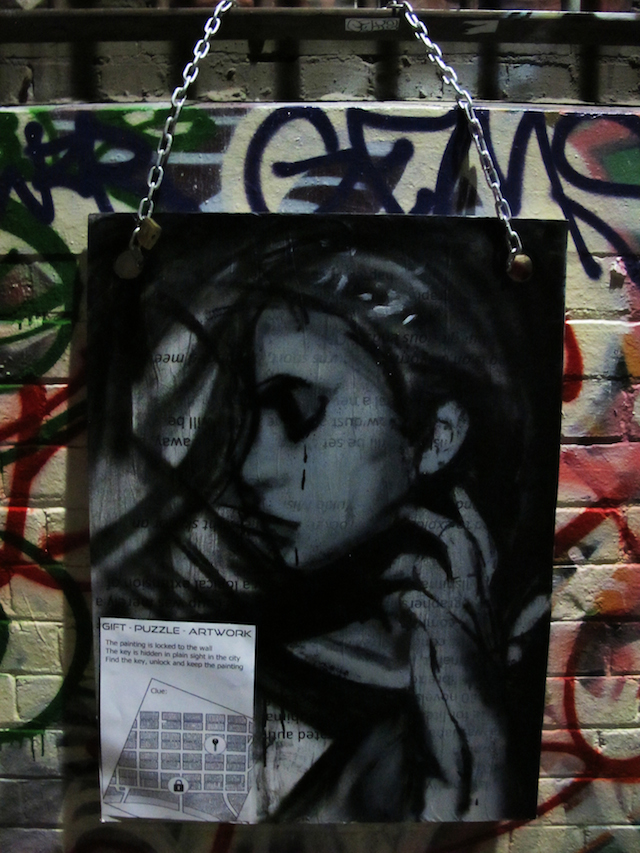

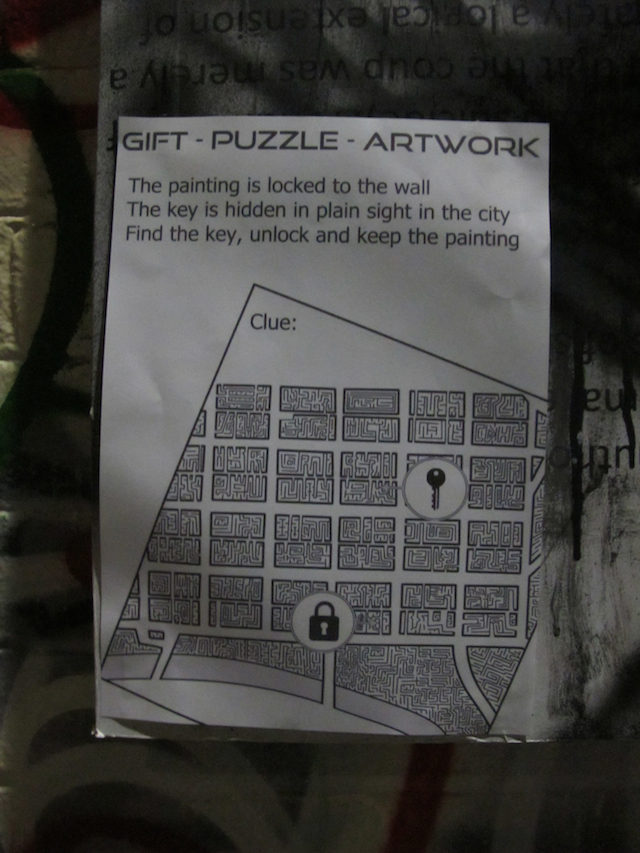

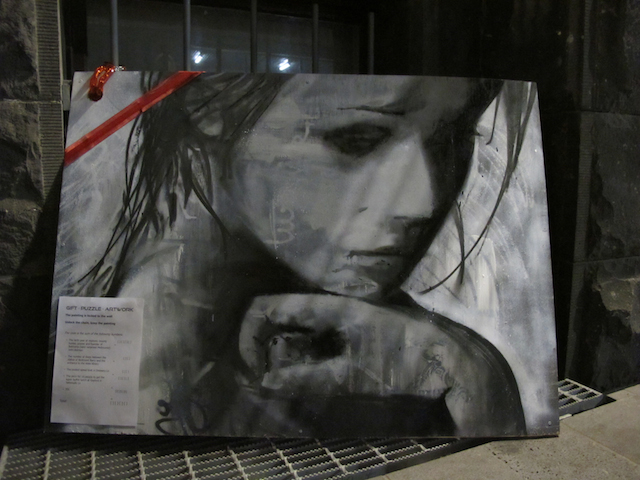

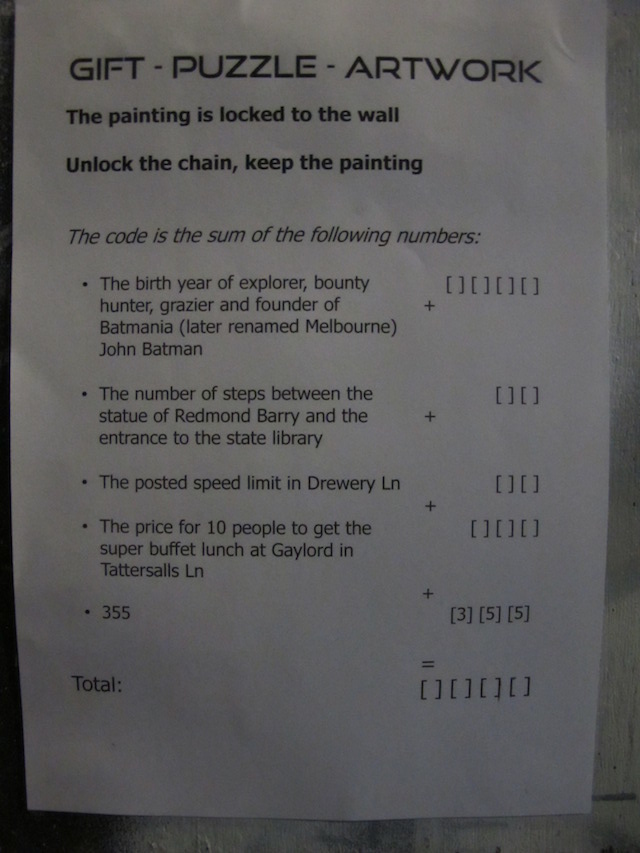

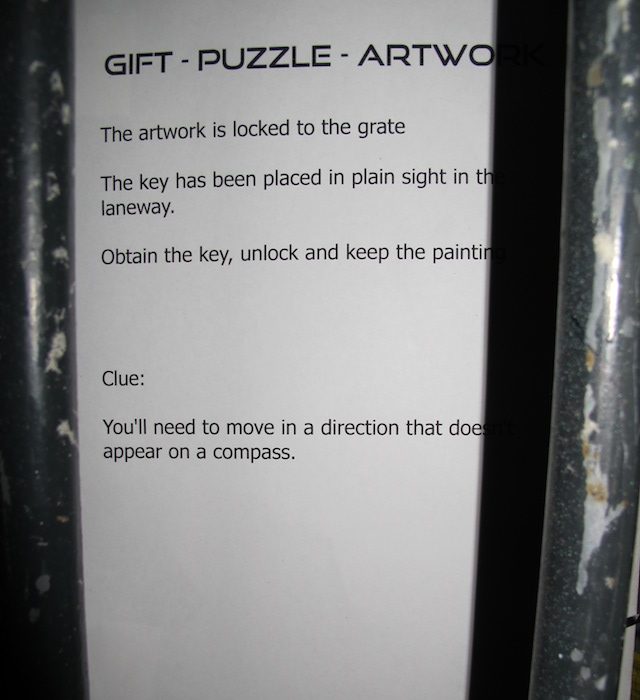

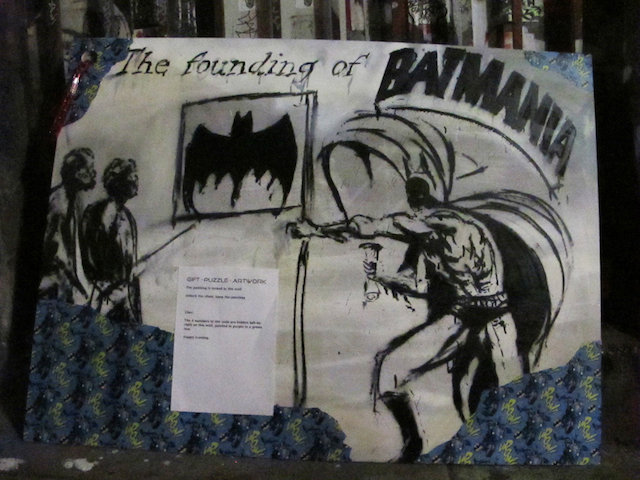

I painted aerosol portraits onto wooden board and pad-locked them onto walls in Melbourne. I then hid the key somewhere in the city and left a puzzle to the key’s location, with the instruction “find the key, unlock and keep the painting”. The clues required participants to hunt and climb within the forgotten spaces of the city, sometimes scaling the outside of a building to the 2nd floor. I designed adventures, transgressing into the dead-ends within a network of thoroughfares; the unfamiliar within the familiar.

The contemporary art market is often about predicting and defining value and placing additional value into a product. Here, games add meaning through a process of collection, without any modification to the physical artwork. Collectors share in the exploits and audacity of graffiti. Perhaps we could fill a gallery with adventures; an obscurest travel agent where the artwork is merely a souvenir.

Value can be added to art in other ways; some artists cultivate eccentricities to manufacture intrigue. Private gallery curators have always spoken knowledgeably and authoritatively about art; understanding an artwork’s theoretical framework or historical context can enhance an appreciation of it. But it’s worth commenting that audiences have become increasingly cynical to this aspect of art. The audio tour for Better Out Than In pointedly mocked art theory. Images shared online of suffocating crowds around the Mona Lisa highlight a lay audience’s inability to connect with high art, with its complex history and theoretical context. It underscores the rise of art without artistic literacy: folk art, design, low-brow culture and much street art.

Giving something away for free can imply it has no value. Placing a task between the collector and the art demands a sense of worth. But sometimes these excursions became more valuable than the paintings. I posted information about the puzzles anonymously online; the comments afforded a window into the responses of the recipient. One recipient solved the puzzle but then reoffered the artwork; he completed the puzzle for the experience, not the painting.

I painted artworks and gave them away to strangers; in another sense, this idea is the artwork. I hope it’s inherently uplifting. In a similar project, Banksy recently sold artworks from a street vendor in Central Park at far below their market value. Passers-by assumed they were fakes. Although this was widely reported in the media, these reports never showed the actual works that were sold; in both cases the spectacle was the artwork. The idea and the story evoke a feeling, not the object.

The online conversations also shaped this spectacle. One recipient said he felt he should pay something for the artwork and so he gave a donation to the Melbourne City Mission, in lieu of paying the artist. Another recipient announced he was going to sell the artwork on ebay. The online discussion immediately turned against him, as most people argued his actions weren’t in keeping with the intention of the artist. I had to intervene to defend him and say that the work was a gift and he was free to do with it as he pleased. The recipients and I became collaborators in the spectacle and altered the emotions experienced by the audience.

Like this article, I left the artworks unsigned. Attaching a name might make the project appear to be an advertising gimmick; money is one type of payment but social capital is another. So the project remains anonymous, to retain the ideal of gifting and avoid garnering resentment or cynicism.

It leads to another question: what is anonymity in street practice? Typically one identity is merely replaced with another. What is ‘Banksy’ in the mind of the audience other than a constructed identity? Individual artworks can be tied together under this common banner. So much more graffiti is truly anonymous. Graffiti created by artists who we know nothing about; artworks that can’t be linked to other art, because the artists are so far off the radar. Here I withhold my street name and it disconnects the project from a body of work. It’s placed in a lost property box of isolated objects created by forgotten artists.

Gifting has always been central to art. Last year Kickstarter gave more money to the arts than the National Endowment for the Arts, the primary federal funding body in the US. This year Kickstarter will distribute more than double the funds of the NEA. At first glance it appears to be a shocking disparity, but only because there’s a commonly held misconception that governmental institutions are the primary supporters of the arts. In reality, private donors overwhelmingly fund the arts. Within these private donors, individuals contribute 75% of the funding, far ahead of corporations and foundations. It’s commonly unknown that the arts are built on a gifting economy and patronage from private individuals. I also wanted to contribute, in another way, to this gifting economy; a potlatch but where the obligation is returned to society more broadly, rather than an individual.

Initially I selected the most populist and commercial notions of art for the image aesthetic: an appealing, desirable product. I could have just placed $50 in a box. Instead I painted the motif of the beautiful young girl; an image that looks like it’s been lifted directly from a cosmetic advertisement. If art is described as derivative or plagiarised, most people recognise this as a criticism. In reality, most people want art that’s derivative because it’s familiar and easily accessible. To be challenging is confronting and uncertain and it demands critical thought from the viewer.

So I painted attractive young girls and chained them to the street. People came and took them from the street. Abducted them, perhaps. Several of the works were left in the same lane as the site of the ‘Rest in Peace Jill’ tribute mural to Jill Meagher, a woman abducted and murdered in Melbourne in late 2012. So the project inadvertently began to take a more sinister twist.

Later I began to paint works that referenced the European colonization of Australia. No treaties were signed with the native Aboriginal inhabitants when the British colonized Australia. Later the legal principle of ‘terra nullius’ (land belonging to no one) would be enacted. These historical circumstances are particularly relevant to contemporary street practices: graffiti is criminalised under the auspices of property rights, but all property rights in Australia are derived from this Aboriginal dispossession. The illegality of graffiti is built on dubious moral circumstances.

One type of non-commodity exchange is gifting: giving without the expectation of reciprocity. Another type of non-commodity exchange is taking without the expectation of offering compensation, commonly called theft. I hope juxtaposing the two offers some reflection on the history and national identity of Australia.

Photos by anonymous