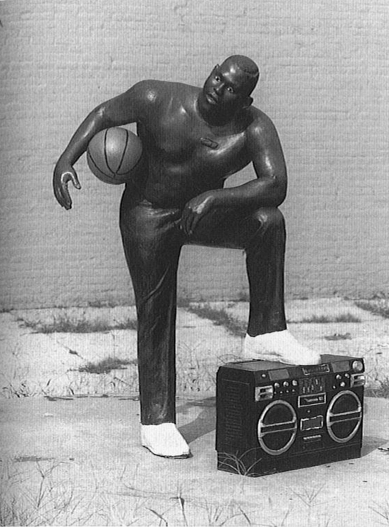

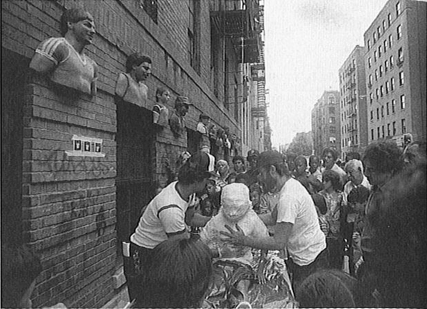

The work of critically acclaimed public artist John Ahearn is as diverse as the models that he casts, yet in retrospect, his work is most commonly known from the community debacle of his three bronzes commissioned for the 44th precinct in the South Bronx.

The contentious issue is eloquently considered in the Jane Kramer essay Whose Art is It (provided here on mediafire) and is very pertinent to Baltimore Open City’s attempt to work publicly. The question is what role does art serve in the public? Does it function best as an affirmative representation of ideals, like many of the massive murals in philadelphia, as an expression of political action or a critical gesture that challenges the perception of its audience? While such questions and their sundry variations may be difficult to answer, when producing work for the public sphere, these modes due warrant consideration. Yet one thing is certain, a cohesive vision of community is in fact illusory, and once the artwork steps into the fray of contending opinions the myriad antagonistic voices clearly differentiate the affiliations that surround our places of living.

In the case of John Ahearn’s three bronzes, after years of deciding the appropriate work and getting its approval for the location, once the pieces were installed, the site became a channel for rhetoric regarding political correctness and representation. The issue was that these were not ideal figures represented in the work, but actual down and out individuals, a reality that the South Bronx dealt with every day but did not want to look towards. In the end the pieces were quickly removed personally by John Ahearn and relocated to the safety of PS1. The empty pedestals became an unfortunate testament to an artist collapsing under the pressure that art should make people “happy” rather than inspire dialogue.