Dan Witz is one of street art’s legends. For more than 30 years, Dan has continued to develop and innovate indoors and outdoors, always staying fresh and above art-world trends. He’s one of the artists that inspired countless others to start painting outside. People, street art obsessed or otherwise, tell stories about discovering Dan’s work by accident.

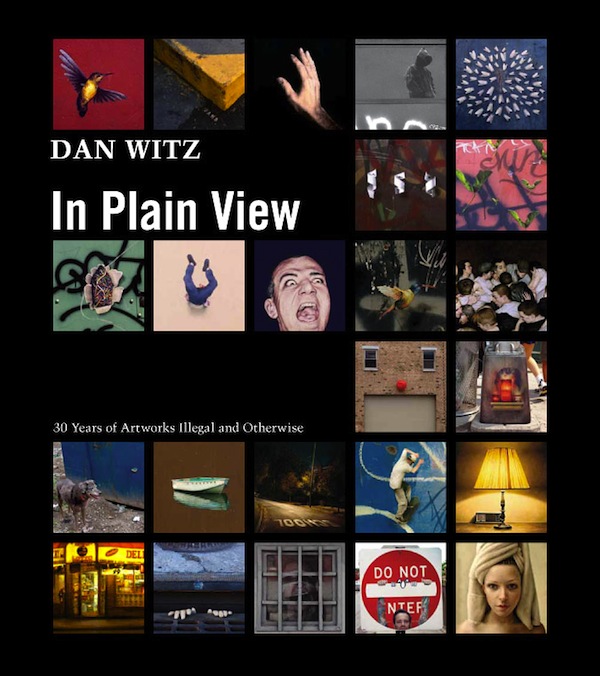

This month, Dan Witz had a massive book published by Ginko Press. Dan Witz: In Plain View: 30 Years of Artworks Illegal and Otherwise is an overview of Dan’s artwork from the 1970’s all the way through 2009, as well as a very in-depth interview with Dan by Marc and Sara Schiller of Wooster Collective. It’s one of the most satisfying art books that I’ve seen, because you really do learn a lot about the artist and gain a new understanding of the artwork without too much effort. I guess that means it’s a successful book, not just a collection of images.

Recently, Dan was kind enough to answer some questioned that I emailed him:

RJ: You’re one of the original modern street artists. Off the top of my head, it was pretty much just Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jenny Holzer and Richard Hambleton doing significant “street art” before you. How did working outdoors start for you?

DW: I got started as an art student in the late 70’s. First wandering around Providence and RISD, then while I attended Cooper Union in New York City. In the days before the internet, our knowledge of what was out there was pretty meagre but I was definitely aware of people who were making street art before me. Charles Simonds did his little people dwellings on the lower east side in 1971. Gordon Matta Clark did his building interventions from the mid 70’s to the 80’s; and there were dozens of artists whose names I never knew. Band posters were big in the east village and were very creative and were generally considered to be more a medium for self–expression than for branding or advertising. Jenny Holzer was in that mix but Richard Hambleton—whose work I really admire–came a few years after I started. And Jean Michel’s Samo stuff, which also appeared a bit after me, I enjoyed a lot, but it was generally considered to be tagging or graffiti writing, not street art. There was a lot of like minded written stuff around at the time, if not as charming or original.

The first things that cracked my mind open and got me working on the street were mostly not from the traditional art world. First and foremost was the subway graffiti, the bombed train cars, how extreme and powerful and utterly original that was. Photos don’t do it justice. Still some of the most astonishing art I’ve ever seen. Seeing and feeling one of those freshly spray-painted trains come rumbling and squealing into the station was just an awe inspiring experience.

Then there was punk rock, and the downtown NYC band culture I was a part of. In that world, art, especially high art, was not highly regarded—it was pretty much looked upon suspiciously, as most likely some kind of scam. The galleries and art magazines of that time were dominated by conceptual and highly theoretical works: a lot of reading and deciphering of dense coded texts was required to appreciate it. To us it just seemed boring and joyless and smugly exclusionary and totally irrelevant to the reality of our lives struggling to survive. The default setting for young artists back then was total rebellion. Against whatever you had. So it seemed obvious to body slam the pendulum as hard as possible to the opposite extreme.

RJ: I think it was Hrag Vartanian who recently told me that you did some work outdoors before your Birds of Manhattan series, now generally thought to be your first pieces of street art. What were these earlier artworks?

DW: They were leave behinds. Basic message in a bottle street art. There were variations but basically these were tiny bits of interesting urban flotsam I’d collect on my ramblings then set up on ledges or window sills. My pockets were always full of odd stuff I’d find on the street: weirdly twisted bits of wire, plastic toy parts, rubber stoppers, squashed batteries, finials, fragments of pictures…every now and then I’d stop and arrange them into elaborate shrinelike displays. I liked thinking of random people coming upon them and how puzzled they’d be.

For some reason it never occurred to me to photograph them though. For In Plain View, my book, I re-created some of these.

I’m still a magpie, I still collect the flotsam, but I just keep it in jars in the studio.

RJ: Martyn Reed (organizer of the Nuart Festival) wants me to ask: “Why do you think that a tiny hummingbird resonated so much with people. It’s not an obvious choice, but wow did it work.”

DW: Resonated…I like that word. it’s a good characterization of what happens when the two worlds combine–the resultant harmony I’m looking for when my imagery integrates with the urban environment. But actually, now that I think about it, harmony’s not quite accurate: it’s more of a dissonance I’m looking for, a collision.

The hummingbird project was originally called: “The Birds of Manhattan: An Industrial Romance.” I got rid of the industrial romance part because I thought it sounded pretentious, but still, that was the concept, the original idea.

For me, painting on the street—doing anonymous, free, non-permissional works–was a very satisfying way of expressing my youthful disenchantment with the art establishment. And the lucky break was that there was a lasting humility lesson in it for me: ever since then I’ve wanted the impact of the work to be felt first, and only after that should you begin to wonder who did it and why.

Also, I think it resonated with frustrated art types like me because it turned out there were a lot of alienated young artists around, and like me, they were just beginning to realize how dissatisfied they were by the art culture of the time. What started out as a somewhat juvenile need to commit the worst art crime I could: painting something beautiful-and meaning it—developed into a life’s work.

I still love the idea of beauty as subversion.

RJ: What ties your artwork together over the last 30-some years?

DW: Good question. Ummm…you know….I don’t think it’s really my place to be the one who holds forth on this. I mean that would suggest that I’m operating under some kind of unified theory or master plan—that I have an art historical identity picked out. Which I don’t. And which I’m pretty sure most artists don’t.

If anything, I’d suggest that there’s a consistency to my interest in realism, the way I’ve tried to keep representational painting relevant (to me) in the post modern era and now the digital age. If some college is ever mis-guided enough to hire me as a teacher, the course I’d want to teach would be called: “So you’ve studied hard and learned to paint. Great. So how are you going to make it relevant in today’s world?”

RJ: Why do a book now?

DW: Uhh…Because they asked? Wait, are you suggesting this is a bad time to do a book? You know…now that you mention it, I’ve noticed that there are a lot of books around about artists like me these days. Does that mean there’s a glut? Will mine get lost in the deluge, and so hence my secretly hoped for little niche in art history? Should I hire an image consultant and start Tweeting or something?

Seriously, my so called career was a lot worse when I was actually concerned with it and trying harder. By now I’ve arrived at the point where the only reliable thing I can do to forward my cause is to show up in the studio every morning (EVERY morning, Tiffaney) and do the work. Oh yeah- and answer e-mails. The rest is pretty much out of my hands. I like this book though. I think they did a fantastic job. Actually, at first I was a bit wary of it because it ends, you know? There’s no wrap up, it just gets to 2010 and on the last page I thank my dog. Which suggests what?–that I’m supposed to be starting some kind of major new chapter in my life now? That I should be entering some kind of fancy middle period? I’m just sorry that this summer’s street art: What the $%#@? (WTF), and my new mosh pit paintings missed the deadline and couldn’t be in the book.

RJ: What do you think about this resurgence of street art in recent years? Is it really a resurgence or just a re-commercialization? It’s not like street art was ever gone, it just seems like the galleries ignored it for a while and now Shepard Fairey and Banksy are taking over museums.

DW: It’s always been puzzling to me that it ever went away at all. I mean it’s so obviously a fertile medium in so many ways. You don’t need a studio and you don’t have to be charming or know the right people to get your work out. And it’s a total blast to do.

I’m embarrassed to admit it, I mean I know I’m supposed to be some kind of wise veteran of the ups and downs etc., but I’ve pretty much survived psychically by keeping a heavy filter on the above questions. I’ve found that too much of that kind of information can be seriously undermining to my optimism–which is something I badly need to keep on with my work. I usually answer these kind of things by saying that I’m not a spokesman for street art.

RJ: Could you describe the difference, if there is any for you, between painting for galleries and painting outdoors?

DW: Pretty much all the artists I admire were active in other mediums besides painting. Rembrandt and Goya did etchings; Degas did pastels and sculpture; Warhol did films; the list is long. With my street art process I get so obsessively involved with whatever I’m doing that by the end of the summer I’m literally nauseated by it. I long for quiet days in the studio, listening to music and wondering what I’m going to have for lunch. But after being home at the easel for a month or so, the difficulty of making paintings begins to wear me down and I get restless and start missing the instant gratification of street art. I’d like to say the two approaches balance me out but you can see they don’t.

RJ: When I first saw one of your Mosh Pit paintings, I thought it was an HDR photograph. I think it actually had to be pointed out to me that it was a painting. What do you think of photographs as art, as compared to say photo-realistic painting? Do you base your artwork on photos, and what do you feel painting brings to the table that a photograph doesn’t?

DW: Paintings that could be photos don’t interest me. Paintings that are so life-like that they are absolutely believable walk-in alternative universes do. Using photoshop and digital printing and every trick I can from the realist painter’s arsenal, my ambition is to push my work as far that way as I can.

In my lifetime there’s been a revolution in representational capabilities comparable to the invention of oil paint in the 15th century. The opportunities to push on to new forms today are just unbelievably exciting. To ignore them, from my point of view, would be a ridiculous waste. So photoshop and photography have become as important tools for me as paint and brushes. I don’t for a moment consider myself to be a photographer or a digital artist though: these are paintings; I’m definitely a painter.

That said, my paintings look (somewhat like) photographs when they’re reproduced. Actually, I suppose, truth be told, you’re looking at digitized reproductions of a digital photograph of a digital and mixed media oil painting based on photo-shopped digital photographs. But all that’s media–information. These are paintings. Which—stay with me here–is why I love paintings so much. They’re the perfect antidotes to that kind of noise. Paintings are hand-made, one of a kind, fragile objects. Absurd. Extravagant. Intrinsically worthless. And seeing paintings is an experience you absolutely have to have in person—in real life. Face to face. Eye to eye. Direct human contact is the point.

RJ: It seems that you’ve always been good about documenting your artwork. Some people like to photograph and document every piece of graffiti or street art that they see; others seem to think that documentation is unnecessary. Why do you think that documentation of street art is important?

DW: It helps me to let it go. It can be hard pushing my stuff out of the nest into the big bad world, but I find taking a decent photograph helps soften the blow.

Finding street art in real life is difficult for most people. I’m pretty sure the majority of the public is familiar with my stuff through photos. But, unlike with my paintings, I’m totally comfortable with this. Even though the ideal experience is coming upon street art in its natural element, the point is still solidly made with a photo: there’s still that shift in thinking.

Dan Witz: In Plain View: 30 Years of Artworks Illegal and Otherwise is available now in books stores and on Amazon.

Photos courtesy of Dan Witz