Brian Adam Douglas aka Elbowtoe is one of New York’s best-loved street artists, but he also has also developed a healthy and equally well-regarded studio practice. This week, Douglas’ largest and most significant solo show yet opens at Andrew Edlin Gallery in New York City. “How to Disappear Completely” will feature drawings as well as Douglas’ famous cut paper paintings/collages. I’ve been eagerly awaiting this show for at least a year, and now it’s almost upon us. The show opens on Thursday evening (6-8pm) and runs through October 26th.

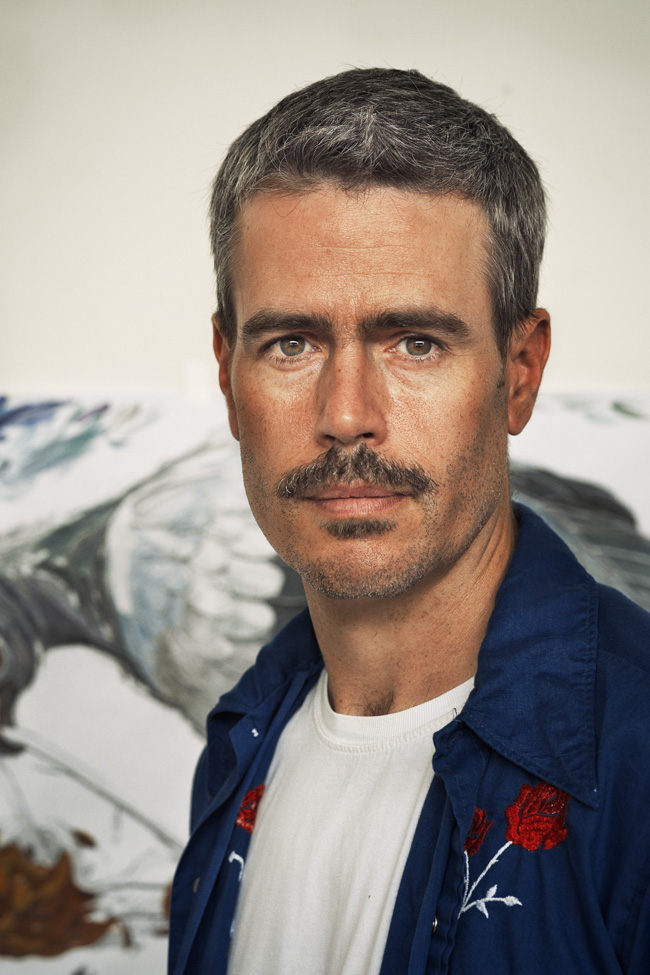

Earlier this summer, Tim Hans met up to Douglas at his studio for the latest in our continuing series of photo-portraits of artists by Tim, and I asked him a few questions over email.

RJ: What can you tell us about your upcoming solo show?

Douglas: This show, at least for me, has been grappling with the end of things.

My close circle of family has been through quite a series of challenges over the past 2 1/2 years, and these struggles have had a profound effect on my psyche. My show is a series of events of great calamity, more often than not after the fact. The protagonist most often rises to the occasion and grapples with the changed environment, though there are occasions that they stand in awe of the devastation before them. The images are on first glance an illustration of destruction, but in actuality are metaphors of redemption.

Though the initial seeds for the images came quite quickly, I have been working out the compositions slowly over time, letting elements slide in and out of focus.

A majority of the work is made of paper, though there is a series of drawings that compliment the cut paper works. I took it as a challenge to make drawings that in their starkness could hold their own against the complexity of the cut paper.

RJ: What goes into making one of your paper paintings? Can you go through the process from beginning to end? How long did the pieces in this show take you to make?

Douglas: For most of the works in my current show, I developed the ideas while taking long walks. My goal is to be a vessel for my imagination, so I am very open to whatever my mind throws at me. Once I get a set of ideas, I begin to research what the significance of the signs, gestures and relationships might offer. This often leads to troves of new information that in turn yields more imagery. My goal when coming up with the images, is to step as far back from the process as I can and literally take notes at what my imagination throws at me. When I have the inklings of an image, I run through a number of studies, and once I find the composition that works best for the image, I get to work on the final drawing.

These drawings can take days, and sometimes weeks to execute depending on the level of complexity. Many of the structures I have in the show are built using old fashioned perspective techniques. The more complex the structures, the longer the study takes. I have one piece with several shipwrecked frigates that I built each with their own vanishing points. They become like scale models. After the drawing is complete, I make a very detailed color study, to establish the proper relationships in terms of light effects and atmospheric effects as well as color and value.

A huge influence on my process is an unfinished painting by Dürer at the Met. In it one is able to really see him working things out. I took his process of the very detailed under drawing from that work in progress. Once I transfer my drawing onto the panel, I comb through my vast collection of paper in search of paper that will build off the color study and other reference that I have gathered. If there are colors that I am unable to find I will make the colors. This is particularly the case in areas of large solid color.

I then attack the image like I would a painting. There is not a set method to the application of the paper. It is a very organic response to the studies as well as all the reference I have gathered. I will say that my “brush marks” are as closely aligned with drawing as they are with paint. I think that the two are inseparable.

When I varnish the pieces, I tend to rub the varnish in, like I am polishing a table. I find this part of the process to be the most stressful. I use a rag to apply the varnish, and I build it up in several thin layers. The difficulty arises from the texture of the built up paper. The surface creates ledges and crevices that the varnish can build up on/in.

The smaller pieces in the show take somewhere in the ballpark of 2 months to execute. The largest pieces took almost half a year in execution, but almost a year for all the elements to accumulate and ferment into the appropriate image.

RJ: You seem like you are always one of the busiest people I know and you spend a lot of time in your studio. What drives you to work so hard?

Douglas: There was a period of time in my life that art was the only stable place I could be. During that time I forged a deep love of the solace of the studio. Since then I have never really been able to shake it. My wife has always been very driven by her arts as well. I think her passion encourages me to work even harder myself. But probably the greatest driving force of my time in studio is that I am always trying to raise the bar on myself with everything I take on, and that just means more work.

RJ: How do you see street art fitting into your practice these days?

Douglas: Sadly I don’t have much wiggle room for street art these days. It has certainly not been for a lack of desire. I have a stack of prints in my studio that we printed this summer, that I have just been waiting to get out. Honestly with any spare time I have I want to spend as much as I can with my twin boys.

RJ: Has having kids changed your art?

Douglas: I don’t know if it has, at least in terms of subject matter. I know it has meant less time in the studio than I used to take. I used them in a street piece. And I made the decision that any time I do any work with them I will make it as off-kilter as possible, find the troubling or unsettled moments. I hate sentimental art, and any time one uses children in art, the artist runs the risk of sentimentality. Having children has certainly made me take a hard look at my practice. I don’t want to waste any time making art that is not worthy of the time I take away from spending with them.

Photos courtesy of Brian Adam Douglas and by Tim Hans