“I was leaving the South to fling myself into the unknown…I was taking a part of the South to transplant in alien soil, to see if it could grow differently, if it could drink of new and cool rains, bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth of other suns and, perhaps, to bloom.” –Richard Wright

Conceptually and visually intricate, Mata Ruda‘s portraits convey a history that is unfamiliar to those who remain unaffected in their daily lives. The idea of el otro, or the other, is something that permeates not only methodologies behind Latin American art history, but the lives of those who chose to emigrate from those countries. While the translation is literal, the word otro encompasses more than that; it’s the feeling of being pushed to the side by the government and others because of one’s origins. Whether undocumented, displaced, or otherwise without a home, these individuals are often left without a voice.

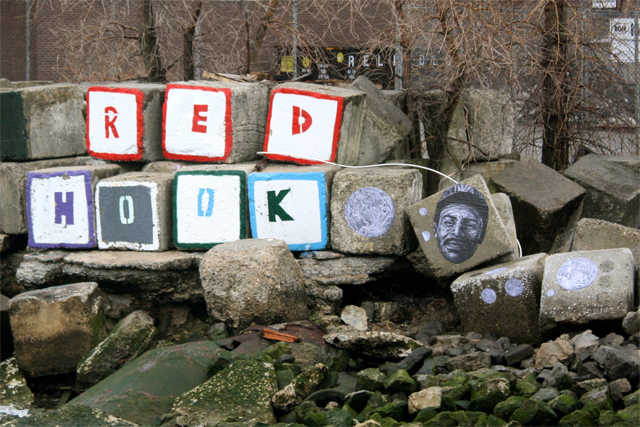

Director Alejandro González Iñárritu explains the feeling of otherness as, “we can’t understand what is happening to ‘something’ if we aren’t looking but nothing is going to happen to that ‘something’ if we don’t look deeply. That’s why so many things with incredible potential go unnoticed…..because nobody bothers to look.” In his most recent series, Mata Ruda draws attention to artisans who would otherwise go unnoticed, traditional Central American weavers who have since emigrated to Brooklyn. By immortalizing these individuals in a public space, the artist draws attention to several underlying issues, such as our lack of appreciation for craftwork, immigration, and labor standards.

Often seen as less than art because of its functionality, this portrait draws attention to the technical layers that makes up the complex patterns associated with Central American textiles. In order to create the zig-zags and vertical stripes associated with these patterns, you must be proficient enough to operate several huddles as well as have mathematical precision in order to accurately reproduce a specific image. This same attention to detail can also be seen in the detailed lines that form the shadows and creases of the weaver’s hands. While the right hand is busy manually picking the weft to create a pattern while the left tests the warp’s strength. It is in this intricate representation of the forgotten that Mata Ruda can be compared to other Social Realist public artists such as Gaia and muralist José Clemente Orozco.

During his life, Orozco saw his neighbors used as expendable bodies in the Mexican Revolution, which he envisioned in The Masses as a sea of faceless heads, yelling but not thinking. The harsh lines that define a field of overlapping reflect the hoards that barricaded towns into starvation during his childhood and eventually led to the loss of one of his hands. For Orozco, he called upon these experiences to give a voice that would otherwise be lost with the pulling of a trigger. A hundred years after the war’s inception, Mata Ruda follows in a similar path, but instead representing the inequalities that run through the 21st century.

Equally as important for Mata Ruda is the representation of homeland and histories. Visually, the artist draws upon the mythology of lunar planning that was integral to his predecessors. Used as a planning tool for practical matters and spiritual ceremonies, Mata Ruda has created portraits that symbolize this importance; the lunar calendars orbit his figure’s head on a series of rocks or become literally placed on their conscience.

It was not enough for the artist to display this meaning in a public space, he also took on a name that would convey this symbology. When literally translated, Mata Ruda means a rough or hardy plant, one that can survive when transplanted like the emigrants he depicts. Beyond the translation, the latter part of his name can be seen as a corruption of the spiritually vital herb Rue. As with lunar charts, this herb is used for its supposed spiritual properties, such as warding off evil and to bring abundance. Through his use of subjects and histories that would otherwise be forgotten, Mata Ruda can be seen as an embodiment of his chosen name. Although paper and wheatpaste may not weather storms, the ideas behind them will last.

Photos by Rhiannon Platt