Recently, VladyArt introduced me to the work of the Italian artist Francesco Garbelli. Garbelli has been working outdoors since the mid-1980’s. While he certainly wasn’t the first to do street art and the term was used in its present meaning as early as 1970’s, Garbelli was certainly active long before the term street art was commonplace, and many of his projects predate by decades similar works by artists that most of us in the street art world are much more familiar with. In this interview, VladyArt asks Garbelli his early work and what it was like to be so far ahead of his time. – RJ Rushmore

VladyArt: Do you remember your first urban intervention? What year was it and how did it all start?

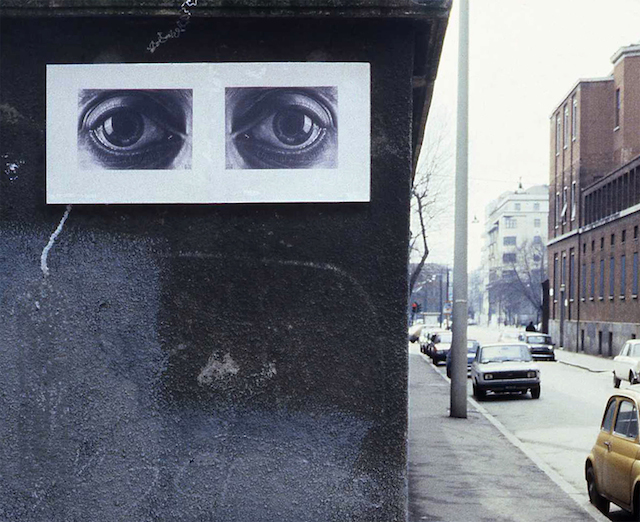

Francesco Garbelli: I started quite early, in the first half of the 1980’s. At that time I was writing poems and songs, and I loved the idea of giving these words the opportunity to leave the sheet for walls and sidewalks. I thought it was the way to maximize the word; I called these “letters in action”… but nobody knew about it. I took pictures of these letters, however, my intention was not being as an artist, yet. As an artist, I started only between the ’84-’85 when, together with a group of other artists, I occupied a large dismissed factory (Brown-Boveri), entering down through a window with a rope. It was a great place to work, and quite central, in Milan. We stayed almost a year, calling dozen of artists afterwards. The place was then reopened to the public, totally transformed by our installations. That was probably the most noticeable artistic event of the decade! One of my installations there was called “altare” (altar) to underline the importance of that abandoned but still “holy” place; my church. Life at Brown-Boveri was very inspiring. My first outdoor works popped up on my way to the university, where I studied architecture, in 1985. They were all located between the metro (subway) exit and the university gate. All streets had names of significant people (such as Leonardo Da Vinci) and I deleted all surnames, making the streets being dedicated to no one in particular: Maria, Giuseppe or Davide. After this, in another intervention, I substituted the person’s name with an image of their work (See Escher). Ultimately on this street name subject, I renamed the streets with sentences and meaningful words (as in “Le lettere vi guardano” = letters are looking at you).

VladyArt: Did you have any role models or artists who inspired you?

Garbelli: No, especially not in the beginning. All it was taken from my studies and cinema. For example, admiring the wild nature taking back the space at the Brown-Boweri factory, I was immediately thinking of movies such as Stalker and Blade Runner.

VladyArt: Did you know other active urban artists in Italy, Europe and America?

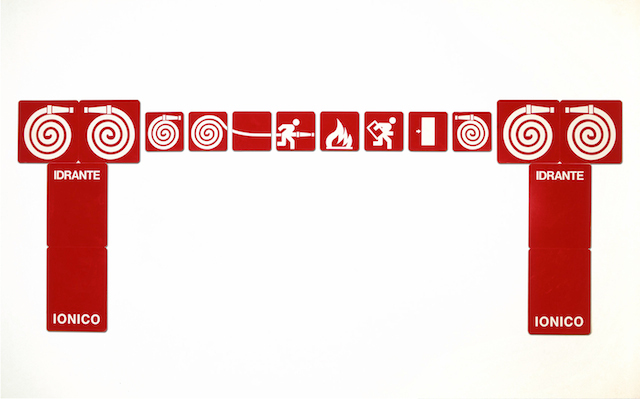

Garbelli: In those years, painting was getting back in the world of art, under the name of Neo-expressionism in Germany and the States and as “Trans-avanguardia” in Italy. This return was totally welcomed by the art biz. I wasn’t exited about that, however the phenomena were pretty cool: people got back to painting and playing guitar like in the 1970’s! I felt very distant from conventional painting, so much that in 1988 I did the “!” danger sign; underneath the triangle I wrote “Neo, Post, Trans,” meaning beware of post/trans-avanguardia and Neo-expressionism. Providentially, in the States was emerging a new art scene, a fresh air breath: Rammellzee, A-One (Anthony Clark), Futura 2000, Richard Hambleton, Kenny Scharf, Keith Haring… just to mention a few. The term “street art” did not exist or I did not know about it. We called it New York Graffiti. We knew about the Lower East Side movement or as the Hispanic were saying “Loisaida.” We knew graffiti: some Americans came to Milan, especially at Salvatore Ala gallery. I actually briefly met Rammelzee, A-One and Haring. I remember particularly A-One, asking, “Are you an artist or a graffiti writer?” to anyone while shaking hands. I understood that for him, the difference was beyond art, it had a social value within. For me it was a bit different: I was not a painter such as in canvas making, extracting bits from Picasso or Carrà, but I was not that urban graffiti type of guy either. I needed my way, a less instinctive approach certainly, and that’s how I got closer to road signs.

VladyArt: So why road signs?

Garbelli: Aside from the historical reasons already mentioned, I have found interest in road sign for their international appeal, the communication made without the words, their attempt to substitute the language with images; a sort of revenge by the old pictography. I was fascinated by some native North American tribe that used knots on ropes or tags on woods to communicate basic concepts; but that’s how our road sign system works! I took the opportunity to launch ironic, fantastic and critical messages through road signs.

VladyArt: How did the people and your colleagues react on your art expression?

Garbelli: Opposite and polarized opinions. It was cool for many, while others were wondering whether road signs could be art or not. With the most of my interventions, I got the attention of the media. However, due to the nature of my uncommissioned (and unsigned) installations, I wasn’t aware of that attention in real time; I couldn’t follow the feedback like people can do today via internet. There was much more surprise when buying the papers and finding my latest work on it. In Italy, beside the Macam (an open air contemporary museum in Maglione, Italy), there was not much availability or interest. My really first interventions done with permission were made abroad, in Holland and Germany, were they let me realized my installations without that ton of nonsense bureaucracy we used to have (City Council, local police, fire dept., Church or so!).

VladyArt: Have you been influential to some younger artists, on your opinion?

Garbelli: I wouldn’t know. The first time I noticed this possibility was by the end of the nineties. I remember two particular episodes, closer to one another. In both cases I was introduced to some younger artist and both told me to have been my fans. As that sounded pretty weird to me at that time. I managed to answer to one: “I guess you had a difficult childhood then,” and we both started laughing.

VladyArt: How did you make connections within the art community? Physically or even by mail?

Garbelli: Well, Milan in the 1980’s was really hectic and full of parties; we were basically going out all nights. Hedonism and yuppie were not my cup of tea, but the city was truly full of events and opportunity. We gathered pretty easily. Otherwise we used the phone, fax and even letters, especially for sending catalogues, pictures and projects.

VladyArt: What’s your opinion regarding this “explosion” of interest in urban art and urban artists?

Garbelli: The growing success of urban artists (and their art) is the combination of several factors. Certainly, the public opinion has changed dramatically, in a positive way. Today there are plenty of festival and exhibitions about public/street art and this is not only considered acceptable by the people but even strongly encouraged by the authorities. In the 1980’s, the public opinion was hostile and my interventions were marked as vandalism by many, even if I did all so graphically and “clean.” From the authorities and the police I noticed about the same attitude but certainly there was less territorial control compared to today. I had no CCTV on my neck. But mostly, today’s boom is thanks to the internet. The public can see all your stuff; artists can form communities. Isolation isn’t a problem, all can happen in real time. I think this has been decisive. On top of that, consider TV; while the “other” art isn’t truly media-friendly for its contents and tempo, (it’s a hard topic for TV formats), street art is photogenic, camera friendly, young and it fits perfectly. This helps the spread of street art via TV, which is globally still the most popular information tool of our times.

VladyArt: Have you got new project and installation for the near future?

Garbelli: Yes absolutely, and I will keep you posted about it. Milan will host the 2015 world expo with the theme “nourishing the planet.” I am conceiving a new outdoor installation about the tribal world, the only people who are doing effectively something to help and save the planet, despite being unaware about it. My world, our modern world, is outlined by Non-Places, characterized by ignorant and criminal minds and their visual rapes; as I feel more and more out of the place, I find it appropriate today to care about these people.

Photos courtesy of Francesco Garbelli